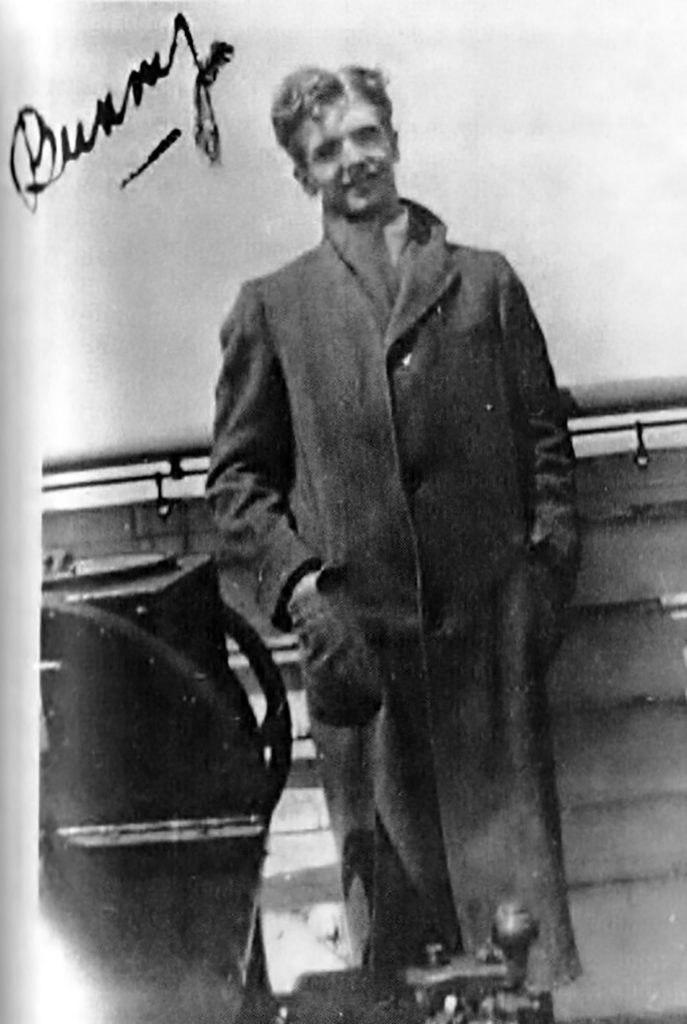

In 1939 the Berigan Orchestra broadcast from the Hotel Sherman in Chicago on the Mutual Radio network as heard in a clip below. The notation suggests this was, “one of the best (if not the best band Bunny ever had).”

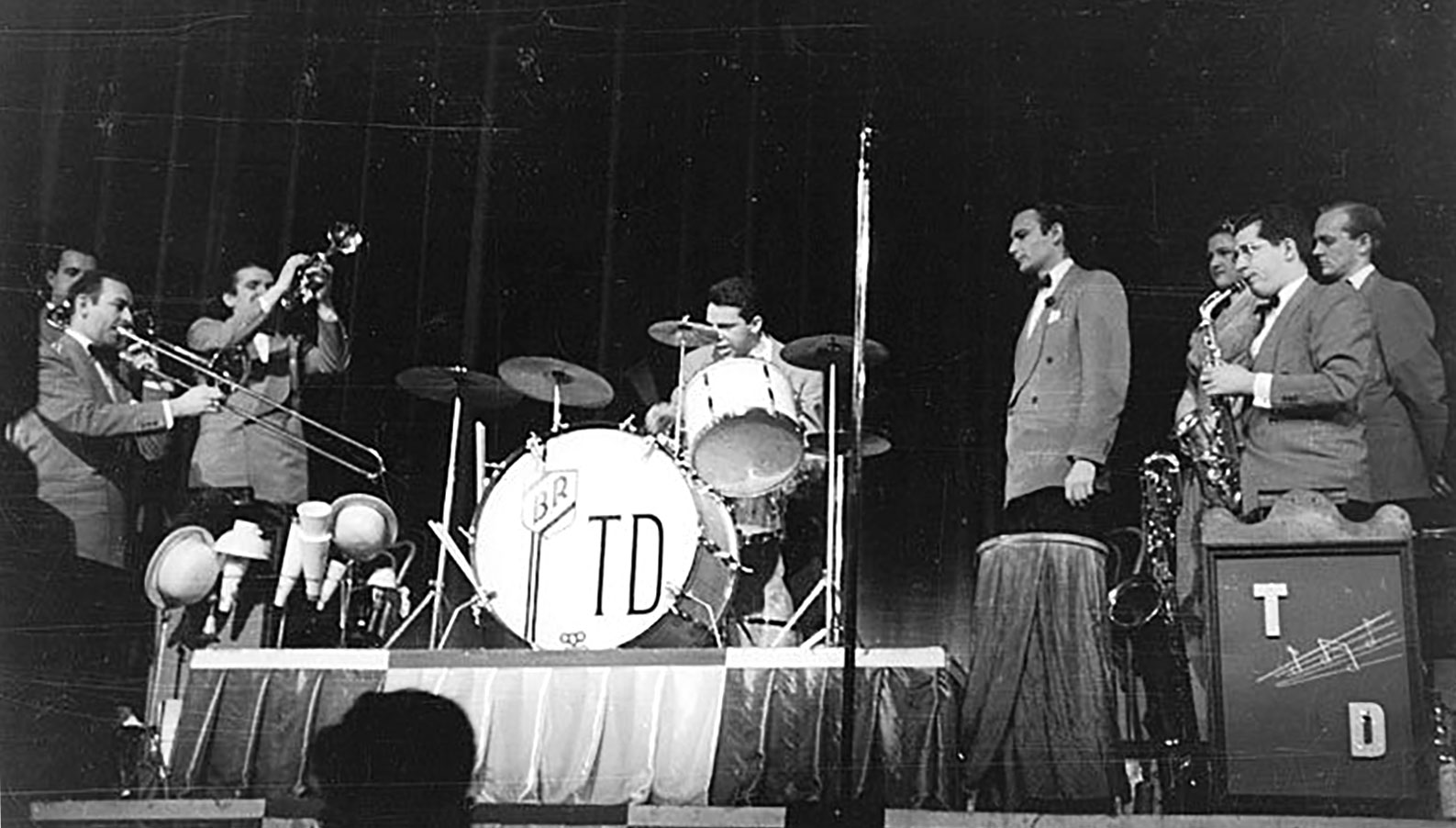

Notably, in launching the enterprise Berigan received considerable assistance and support from his longtime friend and mentor, trombone player and bandleader Tommy Dorsey (1905-1956). Dorsey was a superb jazz musician — despite becoming one of the most bankable names of Swing and Big Band music. In an extraordinary gesture of devotion, he chose to assist Berigan’s orchestra for a season, working as a sideman and manager.

Bunny’s outfit contained several excellent and then-notable soloists. Among the best was Georgie Auld (1919-1990), a Canadian-born Coleman Hawkins-inspired tenor saxophonist. He imparted a bright tone and lightness to many of the Berigan records, before moving on to join Artie Shaw and then Benny Goodman. Much later, Auld appeared in and was heard prominently on the soundtrack of the 1977 motion picture “New York, New York.”

Clarinet player Joe Dixon enthused that the ensemble had “sizzle, real élan” and was “the best band in the country at that time.” Band pianist and arranger Lipman felt the orchestra got a “lotta love,” saying that everybody wanted to play with them. But Dixon said that Bunny’s leadership role “made him uncomfortable, isolated from the men.” Drummer Johnny Blowers found his management, “lackadaisical . . . not disciplined.”

A fine trombone player named Ray Conniff was in Berigan’s orchestra and recording sessions of 1938-39. The talented arranger, who produced Pop hits in the 1950s and ‘60s, may well have contributed to the formidable Berigan book. Conniff recalled: “It was a tight little band, just a family of bad little boys, with Bunny the worst of all. We were all friends . . . Oh it was a mad ball. You should have seen those hotel rooms! Ribs, booze and women all over the place.” Berigan was bankrupt within three years.

Berigan’s most productive year in the studio was 1938. About a dozen sessions generated numerous masterworks. Five of Bix Beiderbecke’s tunes were memorialized – including one of the best, “In a Mist,” which was also one of Berigan’s best records. A leisurely interpretation of “Jelly Roll Blues” brilliantly reworks Morton’s gem that had lain fallow for a decade; Sudhalter finds in Berigan’s interpretation unexpected emotional depths and a mood of “lamentation.”

Jelly Roll Blues

In a Mist

Killed by Booze

Whether drunk or sober, Berigan was an incomparable musician. “Even when he was drunk, he’d blow good,” Ray Conniff attested. But drinking made him unreliable and undermined the confidence of his employees, employers and peers. After dissolving the orchestra in 1940 Bunny worked for other name bands, mostly Tommy Dorsey.

As his alcoholism progressed there were “incidents” of Bunny passing out onstage or falling off the bandstand. By the early 1940s, he was physically wasted and suffering all the horrors of late stage alcoholism: cirrhosis of the liver, edema, tremors, delirium. His dear friend Tommy Dorsey was with him when he died in June 1942. Berigan was 33 years old.

Alcoholism Clip – Sugar Foot Stomp, I’ve Found a New Baby

“Innate Grandeur of Conception”

Fans and fellow musicians were struck by some magic, a special charisma that Berigan conveyed in live performance. Benny Goodman said his presence sent, “a bolt of electricity running through the whole band . . . he just lifted the whole thing.” Jazz writer Richard Sudhalter points to his “innate grandeur of conception, lending a sense of inevitability to whatever he plays.”

Berigan’s music was not calculated primarily to impress, but to serve the musical narrative. True, he was eager to please his listeners and not above using novel effects to achieve his ends through growls, ragged tones, staccato notes, mutes, cups or even hats. Yet each phrase, note or variation in his 600 surviving recordings tends to focus attention on the music rather than the performer.

Squaring the circle of early jazz horn, he brilliantly merged the reflective sensitivity of Bix Beiderbecke and the extroverted power of Louis Armstrong. For a decade of the Swing era, Berigan was one of the most consistently expressive and inspiring talents of his generation. Three quarters of a century after the premature passing of Roland Bernard “Bunny” Berigan, the soaring spirit of his trumpet endures.

Closer Clip – Back in Your Own Backyard, Rose Room, Whistle While You Work, Devil’s Holiday, Panama, theme

Sources and further reading:

Giants of Jazz: Bunny Berigan, Richard Sudhalter (Time-Life Books, liner booklet, 1979)

Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya: The Story of Jazz Told by the Men Who Made It, Nat Shapiro and Nat Hentoff (Dover Publications, 1955)

Jazz Records: 1897-1942 [discography], Brian Rust (Arlington House, 1978)

Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contribution to Jazz 1915-1945, Richard Sudhalter (Oxford University Press, 1999)

The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz (St. Martin’s Press, 1988)

- ← Previous page

- (Page 3 of 3)

For more about Berigan see:

Mister Trumpet

https://bunnyberiganmrtrumpet.com/

Scott Yanow on Berigan

https://syncopatedtimes.com/bunny-berigan-profiles-in-jazz/

Richard Sudhalter’s Lost Chords review

https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1999-02-28-9902280305-story.html

Richard Sudhalter obituary NY Times

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/20/arts/music/20sudhalter.html

Jazz Rhythm Berigan page

http://www.jazzhotbigstep.com/5018.html

Beiderbecke on Jazz Rhythm

http://www.jazzhotbigstep.com/33301.html

Beiderbecke at Red Hot Jazz Archive

http://www.redhotjazz.com/bix.html

Albert Nicholas told me that Bunny was the most respected trumpeter among the colored musicians.

They praised him highly. He was a king. What a waste of talent this alcohol was.