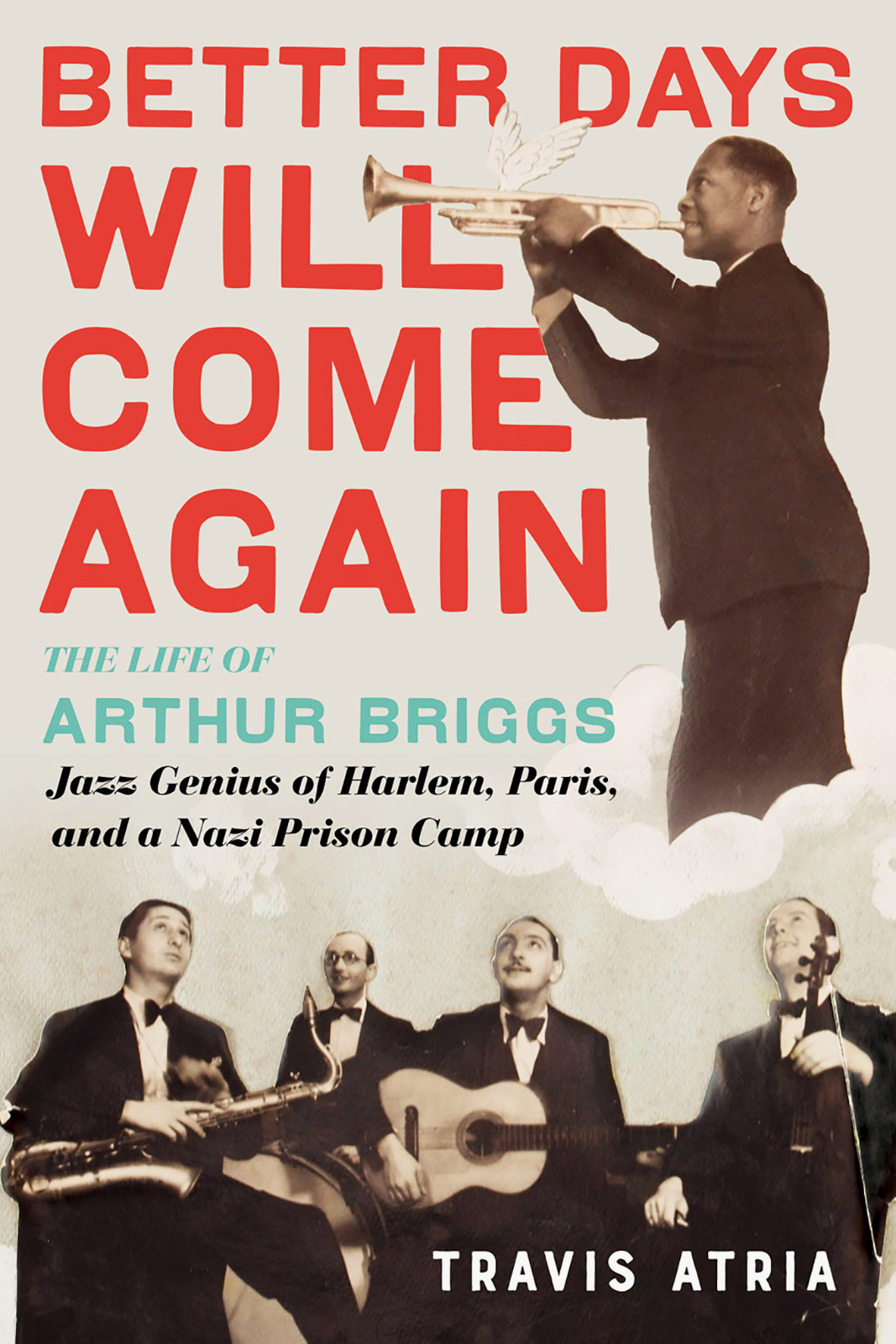

Better Days Will Come Again: The Life of Arthur Briggs – Jazz Genius of Harlem, Paris and a Nazi Prison Camp

By Travis Atria

Chicago Review Press (2020), bibliography and index, 60 photos, 300+ pages.

The book cover is based on a 1935 Hot Club promotional poster with L to R: Alix Combelle, Georges Marion, Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli, courtesy of Denis Pierrat.

Arthur Briggs (1901-1991) was considered the premier Jazz trumpet player of Europe between the two world wars. Living in France continuously after 1931, he deserved his sobriquet “the Louis Armstrong of France.”

A Colorful Tale

This the most exciting and readable new Jazz title in some time, a lilting saga of early Jazz culture and performance in Chicago, Harlem, London, Paris, Berlin and beyond. Written with a novelistic flow, it smoothly traces the arc of Briggs’ stupendous life and career, deftly placing him in both the evolutionary hothouse of early Jazz and the broader context of social history and world events.

Briggs’ close associates were among the most colorful and influential characters of early Jazz: bandleaders James Reese Europe, Will Marion Cook, Noble Sissle and Sam Wooding; dancer and singer Josephine Baker; reed wizard Sidney Bechet; gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt and saxophone master Coleman Hawkins.

Travis Atria is a fresh name in Jazz scholarship, showing great promise. Having previously only co-written a biography of Curtis Mayfield, his insights and comprehensive research bring into focus the evolution of jazz trumpet and Briggs’ growing understanding of his art. I enjoyed the excellent narration in the audiobook format.

Briggs, incidentally, was born on the Caribbean island of Grenada, a fact he concealed most of his life. Migrating to the United States at age 16, he witnessed and participated in the emergence of Jazz in Chicago, Harlem and the black vaudeville halls of New York City. He was one of the first skilled jazz trumpeters heading for Europe — a handsome musician and strapping young man migrating through the wildest environs of the Jazz Age.

Harlem on the Continent

Briggs went to London in 1919 with bandleader Will Marion Cook (1869-1944). Cook was one of the most formidable musicians of the pre-recording era, a bridge from Ragtime to early Swing, and a mentor whom Arthur called “Dad.” Briggs toured Europe with Cook’s Southern Syncopated Orchestra and Sidney Bechet. We witness Bechet purchase his first soprano saxophone. It stumped him initially, so Arthur gave Sidney his first instruction on the instrument.

The Johnson-Briggs Orchestra (aka The Harlemites) was the hottest Jazz outfit in Europe around 1932. Freddy Johnson and Arthur Briggs are far left, Frank Goudie far right.

In the early 1930s, Briggs and piano player Freddy Johnson ran The Harlemites jazz orchestra in Paris. Seated below Briggs in the band photo is Peter Duconge, a close associate of Briggs. A New Orleans-born clarinet player with an illustrious Creole heritage, Duconge married cabaret operator Bricktop and toured Europe with Louis Armstrong. Another Louisiana Creole and Briggs associate was Frank Big Boy Goudie who made his recording debut with this orchestra just months earlier.

The 1933 “Harlem Bound” is possibly the hottest jazz recording made on the Continent before 1940.

Harlem Bound – Johnson-Briggs Harlemites Orchestra

The narrative takes us to the heart of Harlem-on-the-Seine at Bricktop’s Cabaret in the Montmartre quarter of Paris. The Prince of Wales, John Steinbeck and a “zozzled” Ernest Hemingway hang out and carry on while Arthur plays background music for the privileged Americans at the club, typified by Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald. For songwriter Cole Porter, Briggs premiers “Night and Day.” Then he heads for Berlin at the height of its late-1920s decadence, cutting some 64 sides for the Deutsche Grammophon record label.

Waxed in Paris, the masterful “Japanese Sandman” of 1933 probably replicates the quiet, sophisticated duets he played with Freddy Johnson at Bricktop’s. The spectacular “Braggin’ the Briggs” is a double-sided tour de force for Arthur recorded only months before his arrest in October 1940.

Japanese Sandman Briggs & Johnson duet 1933

Braggin’ the Briggs 1940

Detained by the Nazis

Briggs’ story reached a dramatic climax when he was detained by the German occupation government of France and sent to Saint-Denis Internment Camp. Designated Stalag 220, located on the grounds of an ancient gothic basilica and fortress six miles from Paris, Saint-Denis contained about 2000 interned citizens of Canada, Australia and New Zealand, downed English pilots and miscellaneous detained nationals.

Though harsh, Briggs’ confinement was mild by Nazi standards. Red Cross food shipments probably saved him from starvation and his French common-law wife visited, sometimes bringing hot meals. Overcoming severe adversity, they were eventually wed in the camp’s visitor hut.

He was consigned to organizing and conducting music ensembles. These were not like the demonstration orchestras of Terezin or the ghastly caricatures of music ensembles in the death camps. His music was played for the prisoners, and on occasion their captors. The group received a gift of three new trumpets from the Selmer Horn Company.

With his makeshift orchestra of internees, Briggs transcribed Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, performed Mozart and Handel, Strauss and Smetana, covert American songs and “Night and Day,” the tune he’d introduced a decade earlier at Bricktop’s. Arthur often concluded his prison concerts with a spiritual called, “Better Days Will Come Again.”

Aftermath and Legacy

Through it all Briggs conducted himself with the calm dignity, moral rectitude and total commitment to his craft that he evidenced throughout his momentous life. After the war, the trumpeter returned to performing for a few years but soon fell out of step with Modern Jazz. Retiring from professional music, he focused on teaching music and his family.

Late in life Briggs married a much younger woman, fathering a daughter. Directing his full attention to her upbringing, they were very close. His daughter, Barbara Pierrat-Briggs writes in the preface that Arthur helped her with homework and “knew all my dolls by name.”

Methodology

After Arthur’s passing in 1991, the Briggs family guarded his legacy until finding a writer willing and able to impart the scope, context and heart that an authorized biography merited. In an epilogue, his nephew James Briggs Murray makes the salient point that his uncle’s generation built the main edifice of Jazz before 1940, calling subsequent developments “an addendum – based on foundations laid down by those who’d come before.”

Crucial to this book was Briggs’ unpublished memoir based on oral interviews. Mr. Atria cross-checked and fortified it with a broad spectrum of documentary sources, first-hand accounts, wartime archives, the African American press of the day and the substantial body of literature that now recounts events of Jazz in Europe before the Second World War.

My one reservation regards the amount of space devoted to Josephine Baker’s story. Briggs worked with Baker on numerous occasions, but her career was tertiary to his, aside from launching Le Tumult Noir in Paris. Nonetheless, the author often tarries from Arthur’s tale to keep us abreast of her story, even though admitting that Briggs didn’t even mention Josephine in his memoir and suspecting that Arthur disapproved of her loose morals and questionable financial ethics. Baker’s story is uplifting, but I found her close-up cameos a distraction from the trumpeter’s chronicle.

This new biography makes it clear Arthur Briggs witnessed and participated in key developments of early Classic Jazz. For two decades he was a driving force in a Golden Age of Jazz, and the best trumpet player of any kind on the European Continent. When confronted by oppression, he demonstrated character, determination and humanity. Congratulations to Mr. Atria for a job well-done and I look forward to his next effort.

- (Page 1 of 1)

Better Days Will Come Again is a terrific book by Travis Atria. There’s lots of history with fascinating stories interwoven, with more celebrities than almost seems believable, and deep insights to the development of Jazz and Arthur Briggs’s role in this new music. Plus there’s a war story! And stories and insights of the daily and career struggles of a black man during 1920’s through the 80’s.