Willie Lewis_Orch. Willie Lewis and his Entertainers, L to R: Ted Fields, Jack Butler, Billy Burns, Herman Chittison, Frank Goudie, Willie Lewis, Bill Coleman, George Johnson, Wilson Myers, Joe Hayman, Johnny Mitchell.

They performed and broadcast live regularly from Chez Florence Saturday nights on radio Poste Parisien. A Down Beat magazine correspondent — one Duncan MacDougald II –- heard them there in 1938 and suggested that playing for high society might have muted their jazz chops:

“Unfortunately, the group has been playing for several years to a fashionable but dull and unappreciative audience; and at times one notes a dearth of spontaneity and teamwork, which of course is largely due to their public.

But when they choose to settle down and really shell out their best stuff, there is probably not another band in Europe, which can beat them. Recently they blew a special program for the BBC in which the group reached heights of almost greatness.

Willy [Lewis], incidentally, speaks quite good French, is no mean dresser and is one of the hardest working musicians I’ve ever known . . . The weekly broadcasts of the band are, I understand, extremely popular with continental swing devotees, for they play about the only authentic Harlem music to be heard in Europe.”

The orchestra dissolved in late 1938 though Lewis continued performing and broadcasting. In Holland, he witnessed the Nazi chaos that drove most American musicians out of Europe, before arriving back home in 1941.

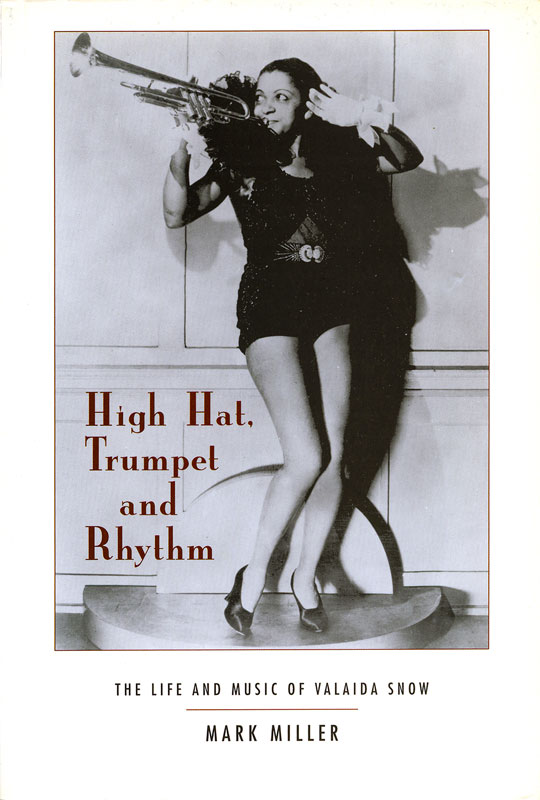

Valaida Snow, “Queen of the Trumpet”

Valaida Snow (1904-1956) was beautiful, show business savvy and boundlessly talented. A hot trumpet player in the Louis Armstrong mode, she was billed as “Queen of the Trumpet” or “Little Louis.” A fine singer, dancer, choreographer and all around theatrical trouper, she’d performed from the Deep South to Shanghai by age 27. The black press often compared Snow with Josephine Baker for her beauty, scandalous lifestyle, international travel and affectations: a pet monkey and orchid colored limousine driven by a chauffer in a maroon uniform.

High Hat, Trumpet and Rhythm: The Life and Music of Valaida Snow by Mark Miller (2007) tells her fascinating story in detail for the first time.

Snow already had considerable success in black musical theater having appeared in the road show version of Sissle and Blake’s “Shuffle Along.” On Broadway in Lew Leslie’s 1930 “Rhapsody in Black,” she did considerable arranging and choreography, besides nearly stealing the show from its star Ethel Waters. In Chicago, Snow was briefly mentored by Louis Armstrong. She performed at the Grand Terrace Ballroom with pianist and bandleader, Earl Hines. They were probably lovers.

High Hat Trumpet and Rhythm, Valaida Snow 1937

You Bring Out the Savage in Me, Valaida Snow 1935

I Got Rhythm, Valaida Snow 1937

Some of These Days, Valaida Snow 1937

But her nearly unlimited gifts went unrewarded in America. Arriving in the mid-1930s Valaida made Paris her base of operations. She was quickly embraced, the publication Jazz Hot declaring in 1936:

“We had the pleasure of finding in Valaida the temperament of the great black trumpeters . . . One is obliged to admire the fullness of her tone and the power that no European musician can even approach.”

Traveling the continent she cut her records in London, Copenhagen or Stockholm. Living the expat life to the hilt she flaunted an opulent, even decadent lifestyle. Her European touring peaked in summer 1937 with appearances on the French Rivera and in The Hague, Holland and Zurich, Switzerland.

Minnie the Moocher, Valaida Snow 1939

My Heart Belongs to Daddy, Valaida Snow 1939

St. Louis Blues, Valaida Snow 1940

Snow was among several black performers who did not leave Europe before the World War II commenced. She was detained by wartime authorities (in Denmark), as were jazz musicians Freddy Johnson and Arthur Briggs elsewhere. Although Snow later claimed that the Nazis had interned her, she spent her last months abroad in Danish protective custody by some accounts, returning home in June 1942.

Quickly regaining her composure, Snow resumed performing until her death 14 years later. Arthur Briggs stayed in Europe after he war resuming his career. Freddy Johnson returned home and gradually swapped professional music for teaching voice and piano.

“A Little Harlem in the Early Morning”

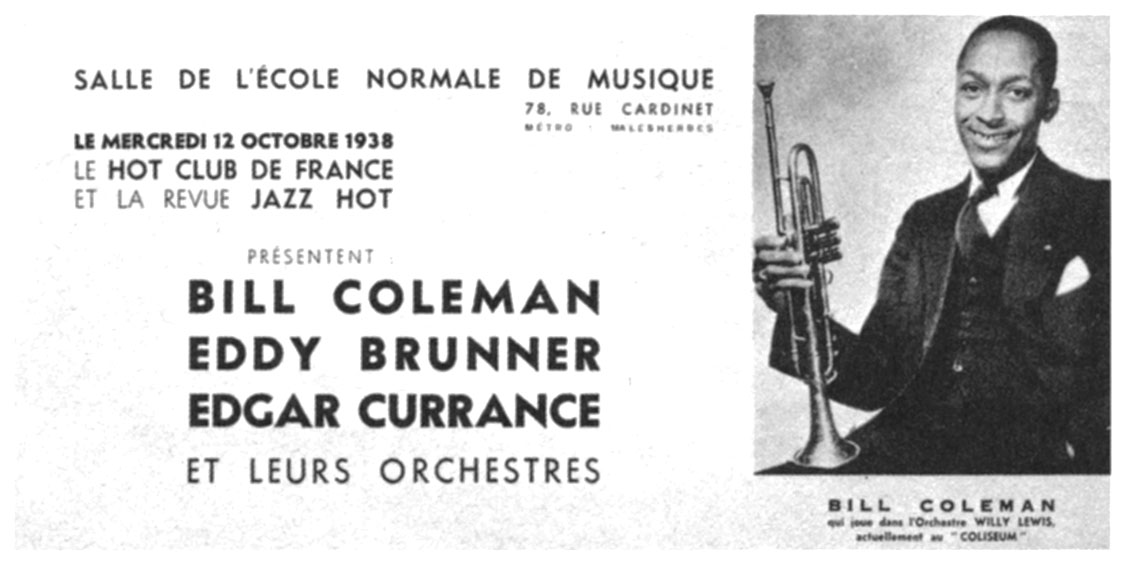

In his memoir, Trumpet Story, Bill Coleman (1904-1981) fondly recalled the camaraderie in Montmartre among the few hundred African American entertainers living in France. They gathered in the early morning hours at, “the bar and hotel Lisiuex’s where many of the American musicians would congregate when they had finished their night’s work.”

Because most black Americans working in Paris were employed in entertainment, it was usually 3:00 or 4:00 o’clock in the morning before their jobs were finished. They gathered at American-style bars and tiny cabarets. Among their favorite spots were The Flea Pit, and Boudon’s Cafe which was memorialized in trombonist Dickie Wells’ languorous “Hangin’ Around Boudon” on which Bill Coleman played trumpet and sang the scat vocal with and Django Reinhardt on guitar.

“Hangin’ Around Boudon” mp3

Daytimes in Montmartre consisted of hanging around in cafes, bars and billiard rooms, or the corner tobacco and postage stamp vendors. Reports Coleman: “Between Boudon’s and Lisieux’s was a little Harlem in the early morning when all the nightspots were closed. The American musicians and entertainers gathered in those bars and the stores with the ‘tabac’ signs.”

Clearly, a great deal of the “Jazz Life” in Paris consisted of sitting around, gossiping, gambling and drinking. American clarinet player Albert Nicholas, cited by Bechet’s biographer John Chilton, had an unromantic memory, “The musicians that I saw in Paris were just hanging around and playing corn, gambling amongst each other.”

But while it lasted, Harlem-on-the-Seine provided for this set of musicians, entertainers and expatriates, “enough of a community to enable African-American members to escape white American racism without also abandoning black American culture,” suggests the author of Paris Noir, Tyler Stovall (1996).

The End of Harlem in Montmartre

As the Great Depression began to bite in the early 1930s, Montmartre nightlife fell off. The decline was hastened by the spread of street crime, a Corsican mafia shaking down cabaret owners and protests from out-of-work French musicians. It gradually sank to a rough trade of prostitution, drugs and gunplay in the streets. The negative side of allowing a thriving Harlem-style entertainment district eventually provoked a strong reaction from the formerly tolerant inhabitants . . . and the authorities.

But by then, the top singers, orchestras and entertainers were finding more prestigious venues outside Montmartre, outside Paris, on the French Riviera or in Monte Carlo. There was work in Belgium, the Low Countries, Portugal, Spain and Germany. Some set off for Egypt, Turkey, India and beyond. And other developments — like Paris discovering Django Reinhardt and a looming German occupation — ended a unique cultural era.

Yet it’s doubtful that American entertainers and musicians (mostly male) in Europe between the wars could have flourished as they did without the fearless, bawdy, talented, outrageous and fabulous divas of Harlem-on-the-Seine who launched “Le Tumulte Noir” and sustained a Golden Age of European Jazz and Swing, 1924-39.

“Bal Negre” 1927. Artist Paul Colin generated more than a thousand images of Josephine Baker collected in a portfolio known as “Le Tumulte Noir.” It made him the preeminent French graphic stylist of his generation.

Thanks for assistance to Dan Vernhettes, and to Mark Miller for consultation regarding Valaida Snow. The story of early jazz continues at the Jazz Rhythm website offering exclusive articles, radio programs and free audio at: www.JAZZHOTBigstep.com

Bibliography:

Bricktop, Bricktop (Smith, Ada) with James Haskins, Welcome Rain Publishers, 2000.

Carisella, P. J. and Ryan, James, W., The Black Swallow of Death: The Incredible Story of Eugene Jacques Bullard, the Worlds First Black Combat Aviator, Marlborough House, 1972.

Chilton, John, Sidney Bechet: The Wizard of Jazz, University of Michigan Press, 1996.

Coleman, Bill, Trumpet Story, Northeastern University Press, 1989 & 1991.

Goddard, Chris, Jazz Away from Home, Paddington, 1979.

Hughes, Langston, The Big Sea: An Autobiography, Hill and Wang, 1993.

Lloyd, Craig, Eugene Bullard: Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris, University of Georgia Press, 2006.

Miller, Mark, High Hat Trumpet and Rhythm: The Life and Music of Valaida Snow, Mercury Press, 2007.

Miller, Mark, Some Hustling This! – Taking Jazz to the World, 1914-29, Mercury Press, 2005.

Shack, William A., Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story Between the Great Wars, University of California Press, 2001.

Stovall, Tyler Edward, Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light, Houghton Mifflin, 1996.

Dan Venhettes, Christine Goudie, Tony Baldwin, BIG BOY: The Life and Times of Frank Goudie, Jazzedit, France, 2015.

- ← Previous page

- (Page 2 of 2)

Ah yes! Valaida Snow. Those songs so good, want to dance just thinking about them. Minnie the Moocher, St.Louis Blues Jazz standards performed by so many. One of my favorite singers today did her version of “You Bring Out The Savage In Me.” Can you guess the name? Give up? Starts with “C” fellow (: