Vivien Garry

The fine bass player Vivien Garry (c. 1920-2008) had a moderately successful career for a decade initially recording for small labels starting around 1944. Garry had high-profile exposure on V-Disc during World War II and on RCA Victor. She then worked with vocalist Leo Watson and recorded for various independent labels until 1952.

Vivien Garry clip (1946) – A Woman’s Place is in the Groove (aka Sycamore Blues), Operation Mop (Edna’s Stomp).mp3

Sophie Tucker

Billed as “The Original Red Hot Mama,” Sophie Tucker (1884-1966) was known for novelties and suggestive songs. Big, bold and brassy, her frankly risqué lyrics shocked and titillated Americans and Europeans alike. As early as 1910 her voice was heard on an Edison cylinder recording. Though not a jazz singer, she was one of the first to introduce jazz songs to white Vaudeville audiences and incorporate syncopation in her style.

Sophie Tucker — He Hadn’t Until Yesterday.mp3

In 1907 Sophie Tucker launched a six-decade career that progressed through Vaudeville, Cabaret, Ziegfeld Follies, records, radio and television.

Ukrainian-born and Jewish, Tucker was also in the forefront of Yiddish popular music. Her biggest hit was a 1928 bi-lingual recording of “My Yiddishe Momme.” It had Yiddish lyrics on one side and English on the flip. She toured the European continent, performing in London for the King and Queen twice — in 1926 and 1963. Sophie was briefly a labor organizer in 1938-39, heading a trade union for vaudeville, circus and nightclub performers.

Tucker was rotund and not considered pretty, which she made part of her act in a song, “Nobody Loves a Fat Girl, But Oh How a Fat Girl Can Love.” She did not do well in motion pictures but succeeded grandly on radio — working her way up to hosting a 15-minute program three times a week on the CBS Broadcast Network in the late-1930s. Her star rose again in the 1950s and ‘60s when she was popular on television, particularly The Ed Sullivan Show. She continued performing until shortly before her death in 1966.

Ethel Waters

African American vocalist Ethel Waters (1896-1977) was the most popular, highest paid female singer of any ethnicity in America around 1930. She deeply influenced a generation of American jazz and popular singers, and was often accompanied on record by the era’s finest musicians and bandleaders, including Coleman Hawkins, Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Benny Carter, Fletcher Henderson and piano player James P. Johnson.

Waters clip – I’ve Found a New Baby (1926), My Handy Man (1928).mp3

Waters had a style and repertoire steeped in Vaudeville, Cabaret and Minstrel music. In New York City during the 1920s and ‘30s she was a superstar of African American musical theater and revues. Ethel was a smashing success in “Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds of 1930,” “Rhapsody in Black,” “At Home Abroad” and singing with Count Basie and his Orchestra in “Stage Door Canteen.”

Ethel broke the theatrical industry racial color line in 1933 appearing in the all-white Broadway show “As Thousands Cheer.” Her music career was gradually eclipsed by acting as she moved successfully into the movies, receiving an Oscar nomination for her performance in the 1943 motion picture “Cabin in the Sky.”

She later hosted her own television show that was nominated for a Prime time Emmy Award. During her last decade and a half Waters toured with the Reverend Billy Graham. Her rendition of “Stormy Weather” resides in both the Grammy Hall of Fame and Recording Registry of the Library of Congress.

Ethel Waters Stormy Weather https://youtu.be/zywZUhaUqMo

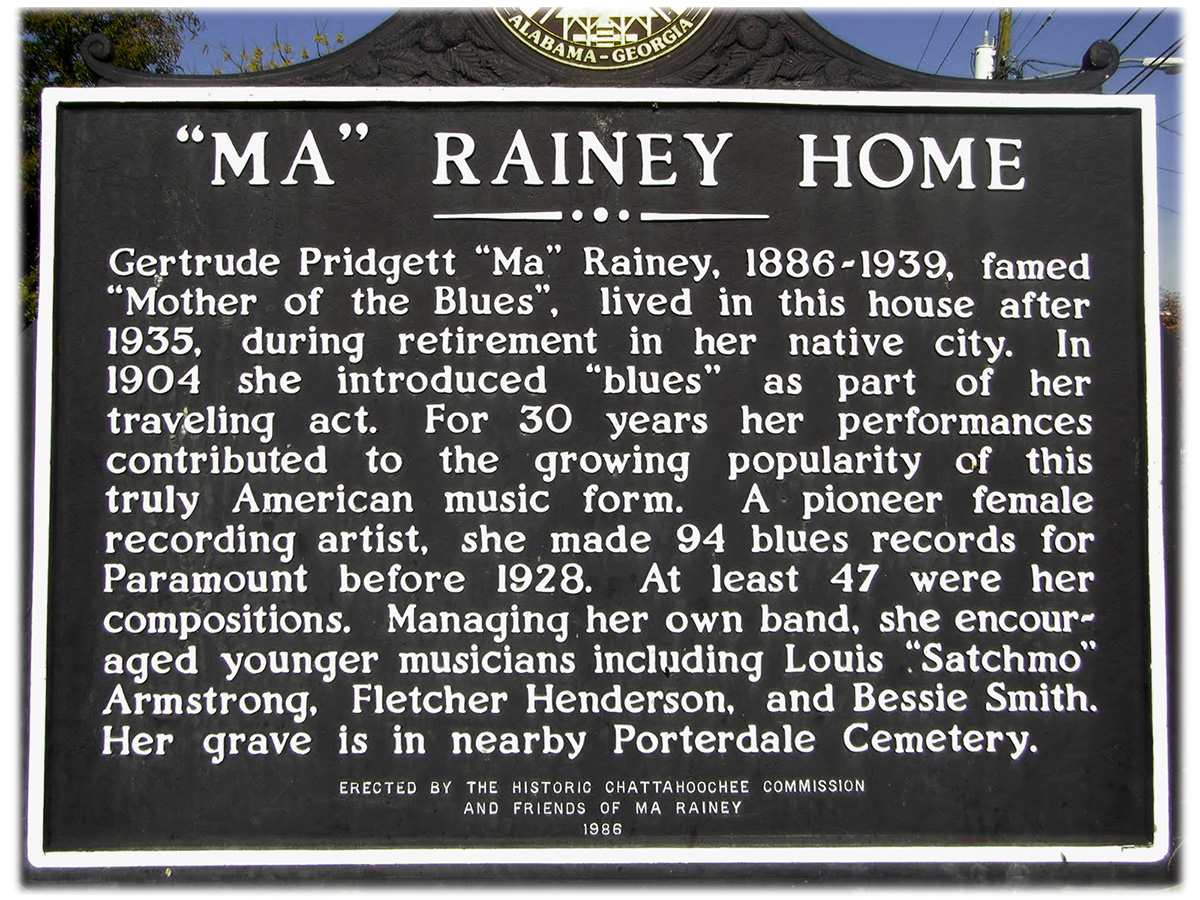

Ma Rainey

The Classic Blues of Gertrude Pridgett “Ma” Rainey (1886-1939) could be bawdy or sad, bold or profoundly heartbreaking. A tough, independent show business pioneer, her powerful voice and forceful personality forged a new path for women’s ClassicBlues. Her records sold best in the deep South where listeners were familiar with her traveling tent shows.

Ma sang with her whole body — her rich, deep contralto voice could rise to a roar without amplification. She flourished a fan of colored ostrich feathers which she used to stress the beat and emphasize her lines with sweeping gestures. For a hot number she’d lift her skirts and dance with surprising agility. The crude recording technology of the era failed to capture the majesty of Rainey’s emotive “moaning” performance style.

Sadly, a large portion of her discs were made with the early “acoustical” system predating “electrical” recordings, which utilized microphones, starting in the mid-1920s. Nonetheless, on her best jazz records, she was backed by Chicago bandleader and pianist Lovie Austin with outstanding New Orleans-born trumpeter Tommy Ladnier and Chicago clarinet player Jimmy O’Bryant.

Rainey clip A (1924) – Lucky Rock Blues, Black Eye Blues, Lord I’m Down with the Blues.mp3

Rainey managed her own business — a caravan of musicians, dancers, entertainers and roustabouts. Her one-time protégé Bessie Smith modeled much of her style on Rainey. But unlike Bessie, Ma didn’t drink, saved her money and was happily married (in her early years).

She was a commanding presence — a sight to behold, both on and off stage. Though frequently described as “ugly,” Ma had an endearing smile full of gold teeth. She dressed in stage gowns covered in beads, bangles and frills, sporting a glittering tiara or headband with an ostrich plume.

Sticking close to her roots, Rainey recorded earthy blues with down-home musicians — like popular blues guitarist Tampa Red or the versatile piano player and composer Georgia Tom Dorsey. Her records were rustic and funky with country guitars, jugs, kazoos and gutty horns.

Rainey Clip B (1927)– Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Oh, Papa.mp3

To her mostly non-urban audience, Rainey was a source of pride, even a spokesperson of sorts — often quietly helping needy musicians or other folk down on their luck. Rainey’s very successful recording career during the mid-1920s gradually declined due to hundreds of imitators, changing public tastes and the falling economic status of her mainly African American, largely rural audience.

- ← Previous page

- (Page 2 of 3)

- Next page →