Traces of Bolden I: Freddie Keppard and Joe “King” Oliver

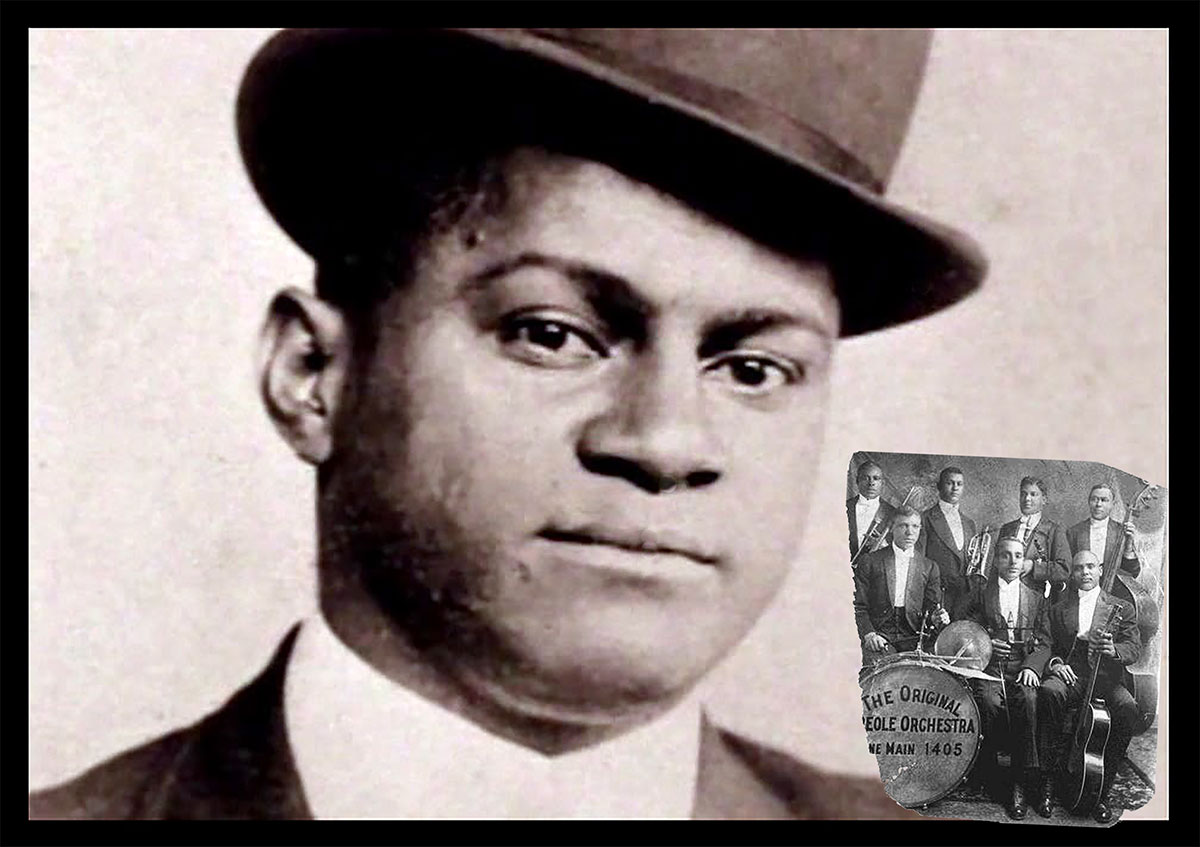

Freddie Keppard succeeded Bolden as “King” of the New Orleans trumpet-playing bandleaders, sharing his style of rough, loud, blues-based horn. Unlike Bolden, Keppard struck out on the road. He visited the West coast with Bill Johnson’s Original Creole Orchestra and then settled in Chicago before World War I.

Freddie, also unlike Buddy, did make records. But common wisdom probably has it right that by the time he recorded his power and brilliance had faded. His style had evolved adapting to current tastes. Yet his 1926-27 recordings reveal glimpses of what must have been a powerful blues-for-dancing trumpet sharing Bolden’s heritage. Convincing recreations of his likely New Orleans-era music can be found on albums by Chris Tyle’s Silver Leaf Jazz Band from the 1990s.

Joe King Oliver succeeded Keppard as King of the New Orleans horn players and the moniker stuck. He continued to reign unchallenged in Chicago during the early 1920s. Yet Oliver developed his own concept of the horn and brought Louis Armstrong in as a second cornet to double the firepower. Though Louis always paid tribute to Joe, there is substantial evidence suggesting that Bunk Johnson was also one of his early teachers — another strong connection to Bolden

Traces of Bolden II: Wooden Joe Nicholas and Lee Collins

Horn player Wooden Joe Nicholas – and other New Orleans horn players from the era who absorbed and retained Bolden’s style — can also guide us to imaging his sound. Recorded in the 1940s, Wooden Joe learned to play cornet by listening to Buddy and followed him wherever he played.

Bringing us close to Bolden’s rough unschooled sound, manifesting the raw soulful power reported by those who actually heard Bolden are Wooden Joe’s “Tiger Rag” and “Sugar Blues” — popular turn-of-the-century New Orleans fare.

Trumpeter Lee Collins is another Bolden follower who recorded during the 1920s in New Orleans. No less than bandleader John Robichoux — Bolden’s main bandleading competitor — called him “a boy with beautiful tone; he is between Buddy Bolden and Bunk Johnson.”

7) Lee Collins & Joe Nicholas Heard him.mp3

Traces of Bolden III: Bunk Johnson

The rediscovery and re-emergence of Golden Age New Orleans trumpeter Bunk Johnson around 1940 galvanized musicians, fans and scholars, accelerating the nascent New Orleans jazz revival. On balance, Johnson may be our closest, richest and best documented estimation of Bolden’s style and repertory.

Johnson was never King of the New Orleans horn players, but could sound like Buddy. Bunk subbed for him when his career was in decline and trombonist Frankie Dusen ran the band. He even recorded the priceless medley of Bolden variations heard below.

In contrast to the majority of these early horn players, Johnson had a proper musical training and solid foundation in Ragtime. Despite the fact that much of what he said eventually proved unreliable, Bunk remains our most direct musical link to Buddy Bolden.

8) Bunk Johnson Remembered Bolden.mp3

Bolden and Women

This is a delicate subject in our hashtag Metoo era. Buddy surrounded himself with beautiful women and loved them. In our hero we discover the negative traits found all too often in modern music stars and public celebrities. As for his actual relationships with women, the data is scarce beyond the fact that he was married and had children.

Bolden was certainly idolized in New Orleans around 1900 and might have been the first American music star with a harem of groupies. His larger-than-life persona, heavy drinking and flamboyant public lifestyle were to become a pattern among American music celebrities and singers from Frank Sinatra and Billie Holiday to The Rolling Stones and trumpeter Miles Davis — or Rap musicians today.

9) Lake Pontachartrain & Milenberg, Rough crowd – Salty Dog.mp3

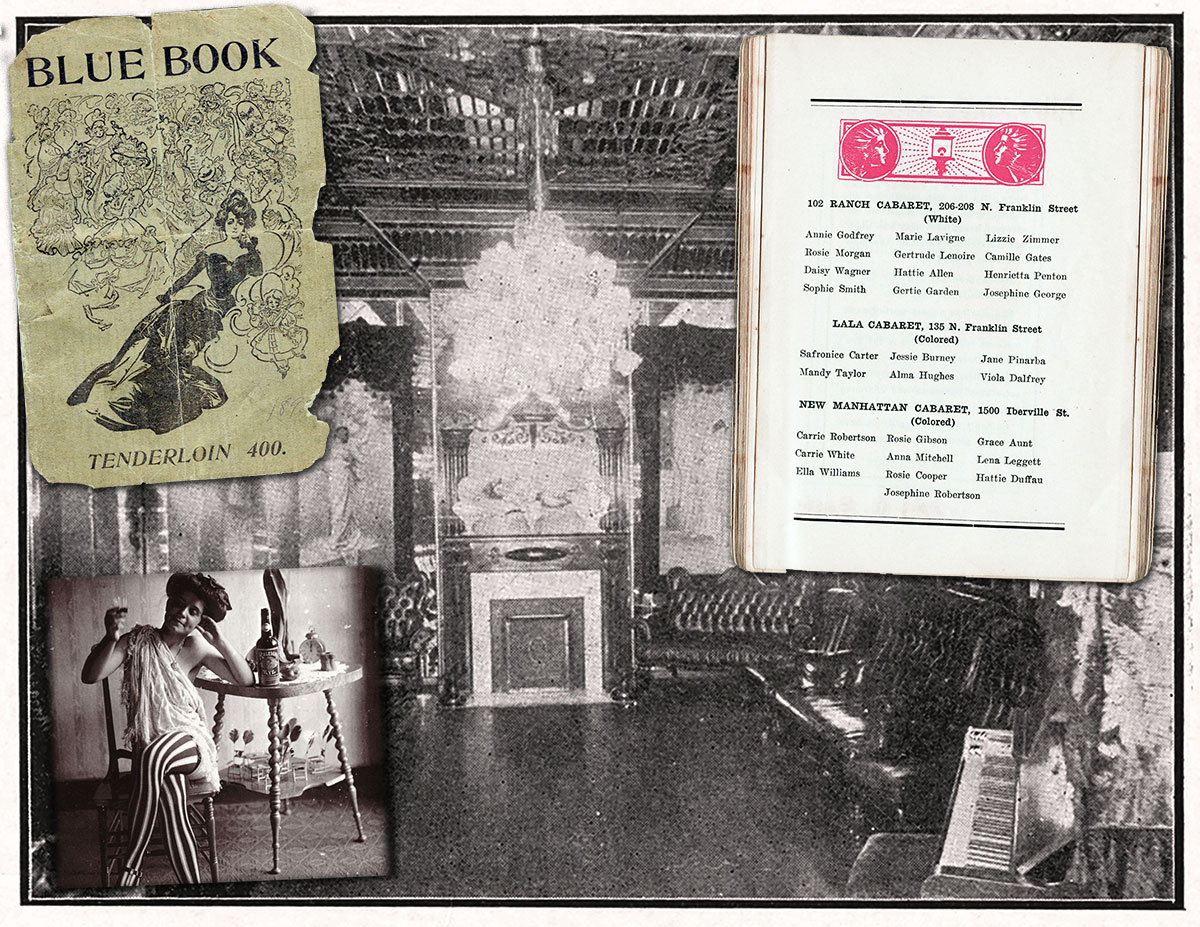

New Orleans boasted hundreds of brothels, photography parlors and bawdy houses between 1897-1917. Above are Blue Book guides from around 1900 and Josie Arlington’s Storyville establishment in 1908.

Bolden was most popular among the so-called Sportin’ House crowd – the denizens and sex workers of the notorious red-light district of New Orleans. Before 1917 the city hosted the world-famous Storyville section containing hundreds of brothels, photography salons and all manner of erotic entertainments.

Buddy catered to a rough, dangerous, demimonde, performing for them Sunday afternoons and Mondays in the parks and lakeside pavilions — or late nights and early mornings in rented halls and lowdown saloons. These are the tawdry facts at the origin story of jazz. Even the term “jazz” itself (originally “jass”) was an unsavory verb prior to 1920, remaining impolite slang until the ‘30s.

Nonetheless, he was challenging prevailing morality when he “jazzed up” a tune or the band improvised bawdy lyrics. Like modern music stars, Bolden was pushing the limits — even in the most promiscuous quarter of North America. The scandalous lyrical variations of Bolden’s informal theme song “Funky Butt” became so salacious and nasty that the local authorities banned it, threating musicians with jail for its public performance.

10) Buddy Bolden’s Blues, aka Funky Butt

Bolden became so associated with the venue known as Funky Butt Hall that locals forgot its original name was Union Sons Hall. The building was used as a church for a while, as seen on the right.

Bolden’s Insanity

Bolden’s protracted end was sad, dying after 25 years in a Louisiana insane asylum. The one major flaw in the Marquis book may be assigning cause and effect to his insanity. Today the consensus is that his mental break was triggered by excessive alcohol consumption, the adult onset of psychosis — or both.

But Marquis constructs an elaborate theory, not unlike Ondaatje, blaming the contradictions of his life and conflicting responsibilities:

“[His] lack of a complete musical education left him vulnerable. . . . What he wanted he was not capable of fully achieving. Neither was he prepared to cope with the overwhelming fame that came early in his adult life.”

11) Bolden Goes Insane and Conclusion.mp3

Traces of Bolden IV: Humphrey Lyttleton and Wynton Marsalis

Recreating the sound of Bolden and his band for a 1986, BBC radio and television documentary, “Calling his Children Home,” British bandleader and jazz horn player Humphrey Lyttleton achieved a landmark of musical archaeology. Aiming for an approximation of Bolden’s ensemble style, trumpet sound, repertoire and format with twin clarinets and bowed bass, his stunning realization is not dissimilar from the 2019 “Bolden” movie soundtrack.

In “Bolden,” jazz trumpet player Wynton Marsalis — in collaboration with producer Daniel Pritzker — imagines both the man and his myth in his original soundtrack and musical direction. Marsalis has championed Bolden’s cause for decades, celebrating him in performance and composition, culminating in commitment to the film.

In “Bolden,” Louis Armstrong is the metaphorical godson of the first jazz pioneer. Satchmo proved to be the best-equipped representative for popularizing and spreading the music worldwide. Today it’s indisputable that Buddy Bolden was Louis’ spiritual grandfather and point of origin for jazz.

Great thanks to the voice actors who dramatized the words of those who knew or heard Bolden: Peter Coyote, Jill Eikenberry, Joe Hughes and Ed Markman. Below are sources for this column and the audio clips. The radio documentary Imagining Buddy Bolden was produced by Dave Radlauer on-air at KALW-FM, San Francisco, California in 1997.

Bibliography and Further Reading:

Barker, Danny Buddy Bolden and the Last Days of Storyville (Continuum, 1998)

Collins, Lee, Oh Didn’t He Ramble: The Life Story Of Lee Collins (University of Illinois Press, 1974)

Foster, Pops The Autobiography Of A New Orleans Jazzman, (University Of California Press, 1971)

Hardie, Daniel, The Loudest Trumpet: Buddy Bolden and the Early History of Jazz (self-published, 2000)

Hazeldine, Mark, Bill Russell’s American Music

Book/CD, Jazzology Press, GHB Foundation (1993)

Marquis, Donald M. In Search of Buddy Bolden, First Man of Jazz (Louisiana State University Press, 1978)

Ondaatje, Michael Coming Through Slaughter (Random House, 1976)

Discography:

Bocage, Peter, Love-Jiles Ragtime Orchestra, “Hilarity Rag,” “B-Flat Society Blues” New Orleans 6/12/60

Celestin, Papa Original Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra, “Careless Love” New Orleans 1/23/25

Collins, Lee, “Damp Weather,” “Tip Easy Blues” New Orleans 11/15/29

Johnson, Bunk, “Bolden Medley” San Francisco 1943, “Make Me A Pallet On Your Floor” New Orleans 4/15/45

Keppard, Freddie, “Here Comes The Hot Tamale Man,” Cookie’s Gingersnaps, “Salty Dog,” “Stockyard Strut” Keppard’s Jazz Cardinals

Morton, Ferdinand “Jelly Roll,” “I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say” RCA Victor 9/14/39, “If You Don’t Shake,” “Buddy Bolden,” The Alan Lomax Library of Congress Recordings 1938-39

Nicholas, Wooden Joe, “Tiger Rag” New Orleans 4/10/45, “Sugar Blues” New Orleans 7/12/49, “Don’t Go Way Nobody”

Ory, Kid, “Oh, Didn’t He Ramble” Creole Jazz Band, Los Angeles 1948

Smith, Hal Creole Sunshine Orchestra, “My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It” 1984

Stanton, P.T. W/ Stone Age Jazz Band, “Tiger Rag” Berkeley 1975

- ← Previous page

- (Page 2 of 2)

Official Bolden Movie site:

https://boldenmovie.com/#home

Syncopated Times:

https://syncopatedtimes.com/buddy-bolden-profiles-in-jazz/

Bolden Cylinder recreation project:

https://youtu.be/ucVxwbbShG0

Other resources:

Three Books About Bolden

https://syncopatedtimes.com/three-books-about-buddy-bolden/

Daniel Pritzker on Bolden:

https://syncopatedtimes.com/director-daniel-pritzker-talks-about-bolden/

Related on Jazz Rhythm website:

Buddy Bolden

http://www.jazzhotbigstep.com/179.html

Bunk Johnson

http://www.jazzhotbigstep.com/319412.html

Humphrey Lyttleton

http://www.jazzhotbigstep.com/24222.html

Joe King Oliver

http://www.jazzhotbigstep.com/58601.html

buddy bolden is my great great great cousin