- Do not rush. (16.20)

- In unhurried motion. Without haste. (9.32)

- Restful. (20.06)

- Very comfortable. (8.25)

4th movement:

We enjoy the heavenly pleasures,

so we avoid all earthly things.

No worldly clamour

is heard in Heaven!

All live in gentle peace!

We lead an angelic life,

yet we are quite merry withal!

We lead an angelic life,

we dance and leap,

We skip and sing!

Saint Peter in Heaven looks on!

John lets the little lamb loose,

Herod the butcher lies in wait for it!

We lead a meek,

innocent, meek,

sweet little lamb to its death!

Saint Luke slaughters the ox

without a thought or a care;

the wine costs not a penny,

in the heavenly cellar,

the angels bake the bread.

Fine herbs of many kinds

grow in the heavenly garden!

Fine asparagus, beans,

and whatever we want!

Whole platefuls are prepared for us!

Fine apples, fine pears and fine grapes –

The gardeners let us have them all!

If you want venison or hare,

down the open streets

they come running!

If there’s a fast-day,

all the fish come happily swimming up!

There Saint Peter comes running

with his net and his bait

along into the heavenly pond.

Saint Martha must be the cook!

There is no music on earth

that can be compared to ours.

Eleven thousand virgins

throw themselves into the dance!

Saint Ursula herself laughs at the sight!

There is no music on earth

that can be compared to ours.

Cecilia and her relations

are splendid court musicians!

The angelic voices

cheer the senses,

so all awakens to joy.

The movement descriptions and lyrics of the 4th movement above may lead one to surmise that the Mahler Symphony No. 4 is a relaxing work. In no shape or form is this true in the scope of the Symphony, although the point can be pressed if put in strict context among all nine of Mahler’s symphonies.

The title of the most tragic Classical/Romantic composer belongs to Gustav Mahler (July 1860 – May 1911), not Beethoven. Although Beethoven suffered ill health in his later years till death, he hungered for life and his works celebrate it; the nine massive symphonies of Mahler are not celebrations of life but reckonings with the inevitable. Mahler was the second child in a line of thirteen siblings, who would eventually lose eleven of them; eight in infancy.

Take the composer’s Adagietto Fourth Movement in Symphony No. 5, for instance, singularly hailed as the composer’s most successful work and often appreciated independently, and yet the symphony opens in utter melodrama. Despite the aforementioned movement, this is not a cheerful work neither. The recording of this work that is universally praised above all others is the 1973 Deutsche Grammophon one conducted by Herbert von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic, now available in downloadable 24 bit, 96 KHz music file from Presto Music.

The Mahler Ninth, as another example, is listed at the number four spot in the top twenty greatest symphonies of all time on the BBC Music Magazine website circa October 21, 2022. Quote: “An epic work from the dying embers of the Austro-German Romantic tradition. Scored for vast orchestral forces – huge woodwind and brass, with a percussion section that includes timpani, bass drum, side drum, triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, glockenspiel and three deep bells – the most striking thing about its soundworld is Mahler’s exquisite handling of sonorities.”

In classical music vernacular, it means the Mahler Ninth, like the other three that top the BBC chart, has the potential above all others to be the fourth greatest symphony of all time in the hands of the most effective conductor and ensemble. Only the most excellent need apply.

Length-wise, unlike the Beethoven Ninth which is the last, longest and grandest among the composer’s symphonic works, the Mahler Ninth is about the same length as his other symphonies and it is not the grandest. For that, his Third and Eighth, the latter famously dubbed the “Symphony of a Thousand” takes the spot. But the one Mahler symphony that is the most misunderstood among his other ones and generally and grossly neglected in standard repertoire is the Fourth. Whereas he sought to convey the one overriding emotion of grief in his works, with the noted exception of his First and Fourth symphonies, Mahler pampers the listener of his other symphonies by alternating themes of lightness and grief so as not to drive his audience into utter despair. But there are no balancing, contrasting motifs of celebration of life versus that of afterlife and resurrection in his other symphonies. To me, Mahler’s symphonies are about his inner struggles for balance between his faith and reality.

From that perspective, the Fourth is Mahler’s brightest gem in all his symphonies, for it is the only symphony among all of the composer’s that is infused with a structured progression from a beginning in the first movement to eventuality in the third. It is also the only of his symphonies that ends with a fourth movement song with full orchestral accompaniment.

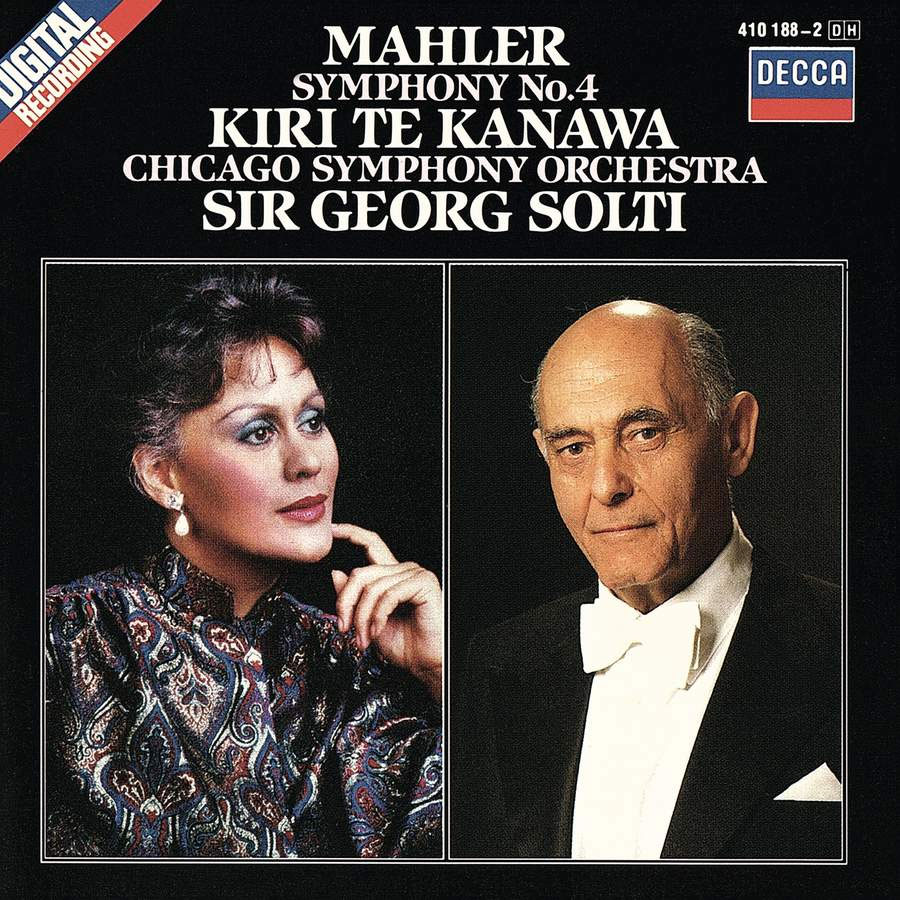

And the one recording that reveals this in the truest, purest form is the Decca compact disc from 1984, performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Georg Solti, with Kiri Te Kanawa in the soprano role. The main attribute that sets this recording apart from all others is the way Solti highlights the distinct thematic intent and communicates emotions in the most focused mannerism among all, and the ever bold confidence of the CSO is in full force in fulfilling Solti’s vision. The delicate vocalization of Te Kanawa is warmly captured by Decca.

The vision of Solti is arguably the most authentic, for many a renowned conductor treated the Fourth Symphony with an even hand, deliberately or inadvertently unifying the moods throughout, intending on presenting the work in its most beautiful form. In my view, the emotions contained in the work are thus blunted, rendering the work sensual, glossy and ultimately not true to its design. Although the Fourth is not about romantic excursions and beautiful notions, it is broader in scope in Solti’s hands than its siblings, and much less severe. Solti shows us how the Fourth is really a descriptive journey on the preciousness of infant life, the fragility of it and Mahler’s narrative of it from his intensely personal perspective.

Sir Georg Solti and the CSO uncoupled the movements from overarching mood, revealing varying emotions from each of the four movements. The otherwise flowing melodic lines as interpreted by most conductors become central dialogs and reflections, flowing directly from the composer’s mind into Solti’s hands, and from his hands into our minds.

The power in Solti’s Fourth stems not only from the crescendos or sheer dynamics but from the degree to which he assessed the correct pacing and mood for the work. While others treated the Mahler Fourth like any symphony by giving it the most lavish and melodic once-over so as to leave an impression of beautiful and vast landscape in the audience’s mind, Solti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra chose not to round off the edges of this highly emotional yet thought-provoking work, or to blunt the seemingly unseemly pacing throughout with a heavy hand in ironing out the upheavals.

When Solti presented the work, it became a virtual twin of the Beethoven Third, a symphony that especially in the Funeral March second movement, conveyed thoughts and emotions through hypnotic, melodic narration that binds the audience to the composer’s innermost self. In the case of his Fourth, Mahler’s spell over the audience is much grander and is expanded into three monumental movements, and the listener is at once ushered into an otherwise pastoral, overall-premonitory introductory first movement, followed by a second movement that begins to impress a steady and slower pace of contemplative state upon the listener. The third movement is the crux of the work, where the composer repeats the motif that warns of pending tragedy in three gradual cycles, until it climaxes in the final minutes. The fourth, final movement reveals the tragedy we were witnessing, the death of a child, for it is elevated into Heaven.

And Mahler didn’t help the matter. For it is in the third movement that Mahler is in his most sublime and powerful, bar none. Within it, Mahler juxtaposes cheerful possessions, thrice, right before stunning us with one of the most devastating passages in all of classical music. Then for a few seconds near the final crescendo he speeds up the orchestra almost as if shuttling the last happy moments of a child faster and faster before our eyes. Then, out of nowhere right in the ending seconds, Mahler wrote one of the most spectacular passages in all his works as the Heaven opens up, marking the child’s entrance. Presence of a fellow listener for companionship during the first listening is advised.

Symphony No. 4’s fourth movement, the finale, is an adaptation of motifs from his 1892 song cycle, Wunderhorn, so thereby the only movement in a Mahler symphony that is a song, complete with orchestral accompaniment, and what a sound and experience it is. The Mahler Fourth is a microcosm of the maestro’s complex emotions, and in Solti’s hands, a direct pathway to the heart of his artistic expressions.

I have yet to encounter a reading more conversational and insightful than Solti’s, and that is due to the fact that no one had wandered from the mainstream, thereby resorting to a convention in which the spirit of the genius is ostracized, and that is precisely how precious and unique Solti’s reading is. Despite all this, the mood conveyed is not complete sadness but solemnity and quiet reckoning. For those seeking comfort and a sympathetic voice, the Mahler Fourth under Solti and the CSO is the only choice.

The one recording I’ve heard that could compare with the Solti is the 1960 Angel release with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Otto Klemperer conducting. Still, Dame Schwarzkopf’s voice was even more recognized and worldlier than that of Dame Te Kanawa’s for the role of a child in my view, though as a soprano she was beyond comparison.

Review system:

PS Audio DirectStream Power Plant 20 AC regenerator

Acoustic Sciences Corporation TubeTraps

Audio Reference Technology Analysts EVO RCA

Audio Reference Technology Analysts SE interconnects, power cables

Audio Reference Technology Super SE interconnects, power cables

Stage III Concepts Ckahron XLR interconnects

Audio Note IO Ltd field-coil cartridge system

Audio Note UK AN-1S six-wire tonearm for IO Ltd

Clearaudio Master Innovation turntable

Audio Desk Systeme Ultrasonic Vinyl Cleaner

Aurender N-1000SC caching music server/streamer

Bricasti Design M21 DSD DAC

Esoteric K-01XD SACD player/USB DAC

Light Harmonic LightSpeed USB cable

Pass Laboratories Xs Phono

Pass Laboratories Xs Preamp

Pass Laboratories XA200.8 pure class A monoblocks

Bricasti Design M28 class A/AB monoblocks

Sound Lab Majestic 645 electrostatic panels

Copy editor: Dan Rubin

- (Page 1 of 1)

I read a lot of music reviews (spanning decades), and indeed the 1973 von Karajan recording of Mahler 5th is highly praised. However, no single recording of the Mahler 5th could be described as “universally praised above all others”. It’s more like there are 4 or 5 recordings that receive consistent praise (the von Karajan being one of them), and the favorites of different reviewers are spread out between the set of top recordings.