A rarely published portrait of Mr. Handy from sometime before 1900. Courtesy of W.C. Handy Home and Museum and Mister Handy’s Blues.

The music, words and voice of W.C. Handy reveal a passion for music, the Blues and African American culture. He dedicated his life to the proposition that the Blues are a legitimate and vital musical form in an era when that idea was rejected or ridiculed. And he was one of the earliest folklorists gathering and preserving the oral and aural folk-Blues, which he successfully incorporated into his songwriting.

This column and audio clips are based on the Gabriel Broadcast Award-winning radio program, W.C. Handy Remembers. Wherever possible Handy’s words and voice have been used to convey his story. Many of the photos are newly available courtesy of the W.C. Handy Museum and Home in Florence, Alabama and Joanne Fish, producer of the documentary, Mr. Handy’s Blues.

Whether they know it or not, most Americans know the music of William Christopher Handy (1873-1958). His lovely “Memphis Blues” and “Yellow Dog Blues” are still popular. A touchstone of American culture, “St. Louis Blues” was the most recorded jazz composition in the early 20th Century. He was variously a traveling minstrel, cornet player, bandleader, promoter, folklorist, composer, music publisher, campaigner for civil rights and cultural icon.

Handy developed a keen skill for creating great music by blending the lyrical fragments and folk idioms he collected with his own gift for composing. His best-known songs like “Careless Love,” “Beale Street Blues” and “Atlanta Blues” were crafted from the raw folkloric elements he dedicated his life to compiling and interpreting. In interviews, articles and his autobiography, Handy always acknowledged his mostly anonymous folk sources.

Introduction and Yellow Dog Blues

Handy on culture:

“When we take these things of our own and develop them till they are the fine things, I think that’s pure culture. You’ve got to appreciate the things that come from the heart of the negro and from the heart of the man farthest down.

The great European classics came from the peasantry of the countries in which these people lived. It didn’t come from the kings and queens and the great theaters. It came from the man who dug deep into the hearts of the people he had come up with and loved, the man farthest down.”

Early Years

Born to a former slave in Alabama less than a decade after the Civil War, William Christopher Handy was the son and grandson of Methodist (AME) ministers. Overcoming resistance from his family and society, he gained a thorough musical education, making his living as a professional musician. During the 1890s, he was a wandering trumpet player (cornet,in the early days).

Handy eventually led his own ensembles, writing and arranging music and becoming a beloved bandleader in Memphis, Tennessee. He started publishing his own songs and was probably the very first to make a livelihood printing and selling the Blues as sheet music, initiating his long struggle to legitimize the form. During decades of roaming, he collected fragments of lyrics, melodies, folk songs, spirituals and work songs, netting like rare butterflies what would otherwise surely have been lost.

Memphis Blues by Handy

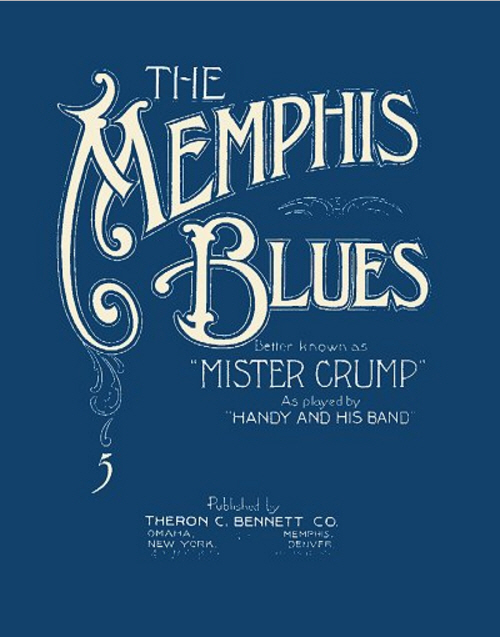

The Memphis Blues

In 1909 his band was hired to play for the mayoral campaign of Memphis political boss, Edward H. Crump. According to Handy, he won the election thanks in part to the popularity of his song known as “Mr. Crump.” Though the politician ran on a reform platform opposing vice and corruption, once he was elected both flourished.

Three years later,Handy put it out as “The Memphis Blues” with new lyrics provided by Mr. George Norton. It was among the very first published Blues songs and a big hit across the country, formally introducing his style of 12-bar blues.

The great success of “The Memphis Blues” in 1912 prompted Handy to form his own company, Pace & Handy Music Co. on Beale Avenue in Memphis. From 1913 to 1918 they published his most popular songs including “St. Louis Blues,” “Yellow Dog Blues” and “The Beale Street Blues.”

Writing the Beale Street Blues:

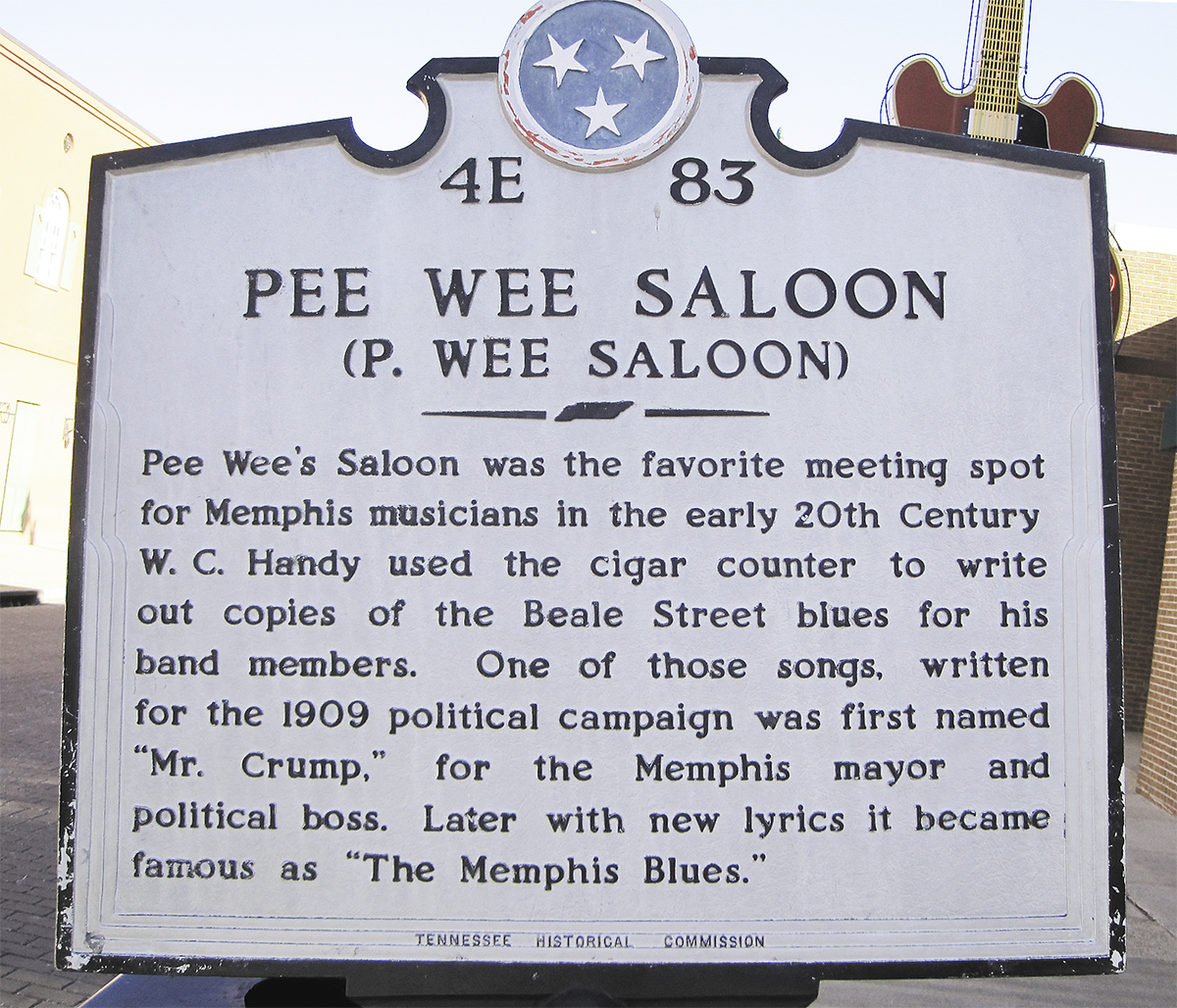

“I like the life of Beale Street. It was exciting. So much so that I was two years trying to write a number called Beale Street, but I couldn’t find words for it.

One night, after leaving my office, I passed by Pee Wee’s saloon. Next to it was a barbershop. This barbershop was open, say about 2:00 o’clock in the morning. I said, ‘c’mon let’s go home.’ He says, ‘I haven’t closed up cause ain’t nobody got killed yet.’ And I struck myself and said that’s it, Beale Street Blues! I went home and wrote the words to the Beale Street Blues that night.”

The Beale Street Blues

Memphis was a thriving transportation hub where the railroads met the Mississippi River. Developing after the Civil War, the original Beale Avenue was a respectable, predominantly African American neighborhood of homes,churches and a grand opera house.

When Handy arrived around 1910, Memphis had sprouted the notorious Beale Street entertainment district, an infamous collection of taverns, pool rooms, dance and gambling halls, brothels and dives. The lawless section was occupied by hustlers, pickpockets, lowlifes, pimps and prostitutes, attracting country rubes seeking thrills and workingmen, riverfront roustabouts, levee workers, cotton farmers and Pullman porters out spending their hard-earned pay.

Thriving in the rough nighttime traffic of the rowdy quarter, Handy was oddly fascinated, possibly even obsessed by Beale Street, observing razor fights, stabbings, ice pick killings, shootings and worse.

You’ll see pretty browns in beautiful gowns,

You’ll see tailor-mades and hand-me-downs,

You’ll meet honest men, and pick-pockets skilled,

You’ll find that business never ceases ’til somebody gets killed!

If Beale Street could talk, if Beale Street could talk,

Married men would have to take their beds and walk,

Except one or two who never drink booze,

And the blind man on the corner singing Beale Street Blues!

Beale St Blues, Yellow Dog

Yellow Dog Blues

The Yellow Dog Blues

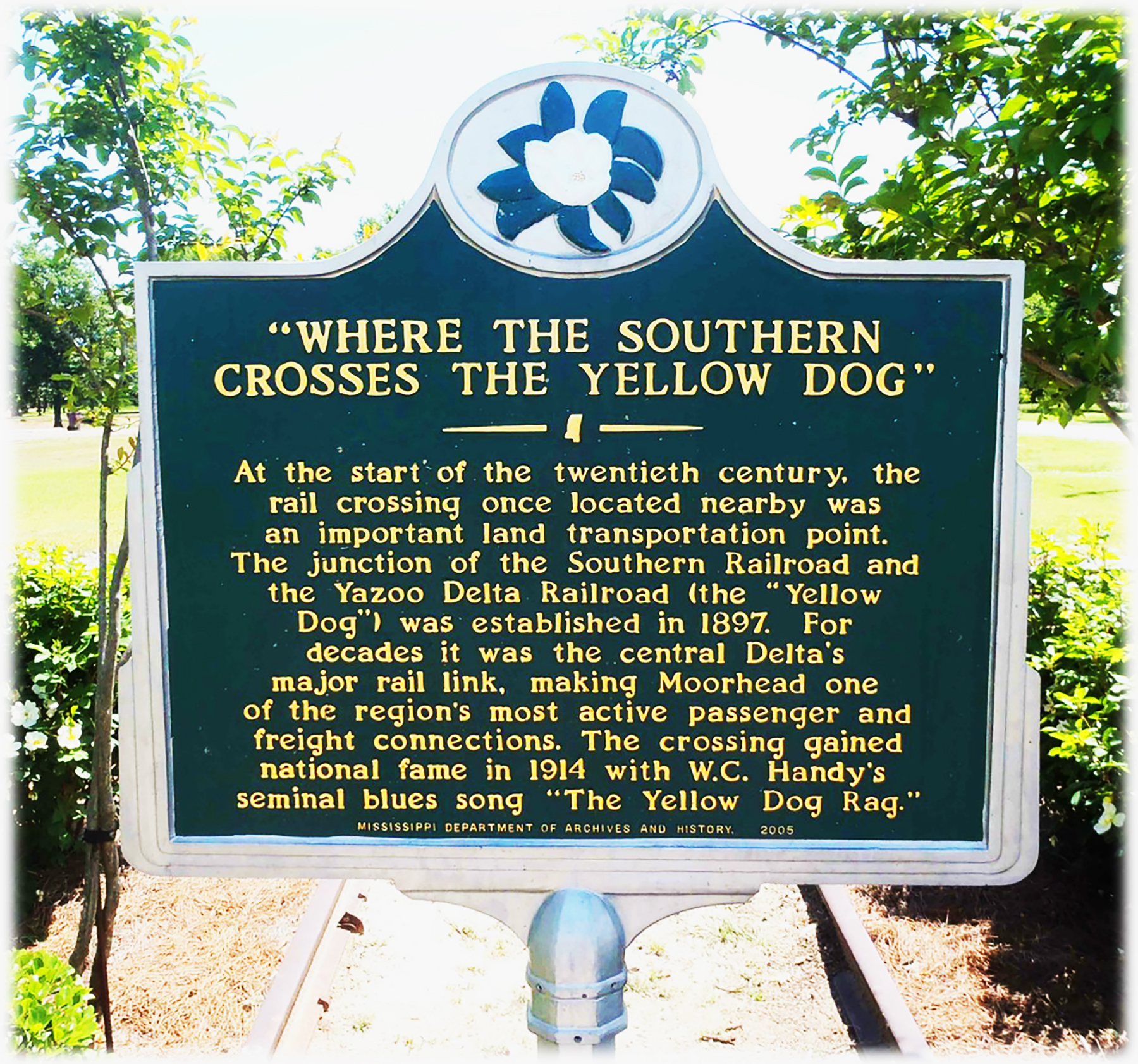

W. C. Handy published the “Yellow Dog Blues” to great success in 1914. One of his simplest and most enduring Blues, it highlights his remarkable skill at carving poetry from the vernacular. He had heard an itinerant singer playing it on a slide guitar a decade earlier in a rural railroad station– a galvanizing early encounter with the Blues.

The song tells the tale – real or imagined — of Miss Susie Johnson, who is lamenting that her“easy rider” (lover, pimp or gigolo) has runoff. The frantic search elicits a letter informing her that he “struck this burg today,” but had left and gone to “where the Southern cross the Yellow Dog.”

Yellow Dog Blues – Bessie Smith 1925

Commentary on Bessie Smith’s Yellow Dog Blues by Dan Radlauer

For a deeper look I’ve asked an accomplished musician, my brother Dan Radlauer, to assess the best-known rendition by Bessie Smith, accompanied by Henderson’s Hot Six (aka Bessie Smith and her Blue Boys) recorded in New York on May 6, 1925.

“The song starts with standard, predictable blues chord changes and evolves smoothly into some complex and rich variations on that chord progression. After the truncated blues form intro, where everyone in the band except the singer is playing, we launch into a very simple accompaniment behind Bessie Smith.

Twelve-bar Blues has become the primary “Blues” form, and this song is no exception. The hallmark of a Blues chord progression is the fifth measure. Various things can happen before or after that spot, but at that point the defining moment is going to the “IV” chord.

Here the cornet plays subtle fills and long notes, keeping the style and mood. The first two verses use the simplest of Blues Progressions. No superfluous chord changes. Just meat and potatoes Blues. Pretty much: I, IV, I, V, I, V.”

“But at the third verse, all bets are off. Each subsequent verse gets more harmonically complex and sophisticated. The third verse uses a VERY unexpected chord at the 9th measure. I don’t think this would ever happen spontaneously. Either it was rehearsed, or there was a written “chart” to help everyone stay on the same harmonic page.

On the YouTube link https://youtu.be/JVL24i38F2s of this song, at about 2:30, listen for a descending line. This is a very distinctive moment and the band executes it beautifully. If you listen really close at 2:45, another special moment happens. The band has hit the important sign post of going to the IV chord in the fifth measure, but in the 6th measure, they switch that chord from a MAJOR chord, to a MINOR chord. While not unheard of, this is a wonderful little surprise and would most likely be planned ahead of time.

- (Page 1 of 2)

- Next page →

I can’t imagine the number of hours it took to bring this magnificent retrospective to life.

Thank you Ted. To tell the truth I’ve been working on it on and off since 1992. Best, D

Thanks for putting all this together, Mr. Radlauer, it’s really remarkable. Love the recordings!