Cartridge compliance

Compliance has to do with the stiffness of the damper the cantilever is suspended from. Think of it like a shock absorber on an automobile. Some are stiff and require more effort to move while others are soft and easy to move. I will discuss why this is important when I discuss tonearm differences. As for why cartridges have different compliances, that is dependent upon the manufacture’s design preferences. Compliance specs are measured in µm/mN (micro meter or micron per millinewton). What that means is how far the stylus moves in microns with one millinewton of force.

Stylus design

I discussed earlier the basic shapes and types of stylus configurations. To elaborate on this a little more, I will begin with 78-rpm records. They have larger grooves cut in the record and require a stylus to accommodate this record design. Typically, a conical tip with a tip radius of 65µm to 70 µm is required. Likewise, 45- and 33-rpm records, which use RIAA equalization (discussed later), have much narrower grooves and require smaller diameter styli.

Above is a cross-section diagram comparing two common types of stylus:spherical (left) andelliptical (right). Note the difference in contact area. The elliptical stylus shape of approximately 0.3 x 0.7 mil allows for more groove contact area, which increases fidelity, whereas the spherical makes less contact with the groove and generates lower fidelity.

Higher end styli shapes have evolved, and tip mass and shape has gotten smaller to allow the cartridge to produce higher frequencies with lower noise and flatter frequency response. It is not unusual to see styli with 0.2 x 0.7 mil shapes.

Additionally, the polish and profile on these styli can be quite exotic. Examples include “Hughes” Shibata variant (1975), “Ogura” (1978), and Van den Hul (1982). Such a stylus may be marketed as “Hyper elliptical” (Shure), “Fine Line” (Ortofon), “Line Contact” (Audio Technica), “Stereohedron” (Stanton), and Fritz Gyger (1989), which is marketed by several different cartridge companies.

Equalization

Early gramophones had very limited frequency response and dynamic range due to the physical limitations of the design. When the magnetic phono cartridge became available in the early 1950s, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) developed a standardized equalization curve for recording and playing back records. Because low frequencies have higher amplitude than high frequencies (for the same perceived loudness), the space used to produce low frequencies needs to be significantly larger, resulting in limited playback time per side of the record. The RIAA equalization curve allows for longer playing time per side.

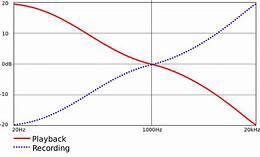

RIAA playback equalization is not a simple low-pass filter or high frequency boost. It defines transition points in three places: 50Hz, 500Hz and 2122Hz. The diagram to the right shows both the record and playback curves as specified by RIAA.

The introduction of electronic amplification allowed these issues to be addressed. Records are made with boosted high frequencies and reduced low frequencies, as defined by the RIAA, and the equalization is inverted upon playback. The net result is a relatively flat extended frequency response with lower noise levels and improved dynamic range. Additionally, it conserves the amount of physical space needed for each groove by reducing the size of the low-frequency undulations.

Prior to 1950, the record industry used many different EQ curves, as every record manufacturer seemed to have its own. Fortunately, RIAA has standardized the industry worldwide.

Turntable construction

There are literally hundreds of variations of designs for turntables. But basically they all consist of a platter to support the record, some sort of motor assembly drive to rotate the platter, and a tonearm to support the phono cartridge and allow it to move across the surface of the record.

Inexpensive record players have typically used a stamped steel platter. Other options include machined aluminum, glass, polymer, and even wood. J.A. Michell turntables use vertical posts with small rubber pucks to support the record.

Normally a mat is used between the platter and the record to minimize vibrations of the record. This is frequently rubber but, again, there is a range of options, including cork, felt, leather, and Sorbothane.

The platter typically mounts on a spindle bearing often made of a bronze or steel. There are variations of this as well. A number of tables use inverted thrust bearings, others use magnetic bearings, and the most exotic I have seen use air or fluid to support the platter.

Most high-end turntables use heavy aluminum castings that have greater balanced mass and inertia, helping to minimize vibration at the stylus and maintain constant speed without wow or flutter, even if the motor exhibits cogging effects.

This is a good time to explain wow and flutter as well as rumble. Wow is a slow variation in speed, similar to a Doppler effect, where the tone varies slightly. Flutter is similar but with faster repetition. Both cause distortions of the music. The lower the figure the better. Finally, rumble is typically the noise produced by the motor and transferred through the playback system. Rumble can also be caused by a poor quality bearing under the platter.

Turntable drive systems

The main reason a turntable may have poor wow and flutter specs has to do with its drive system. I remember when I first started selling turntables the majority of turntables sold were record changers, which stacked 5 or 6 records and dropped them in succession. These included products from Dual, Garrard, BSR, ELAC Miracord, and Perpetuum Ebner PE. Later on, Technics and BIC joined the party. Fortunately, record changers fell out of fashion and have not come back.

Idlerwheel drive systems

Early turntables used idler wheel drive systems. An idler is a rubber wheel that intermediates between the platter and the motor. In the early 1960s,Thorens produced the TD124, which used an idler that rides against the platter but it used a belt drive to connect the idler to the motor.

Another classic was the Swiss company “Lenco”, whose idler wheel ran along a tapered motor drive shaft. This reminds me of a variable speed transmission in cars, which allowed variable speed control on the drive. The Lenco L75 is pictured. These Thorens and Lenco models are the audiophile exceptions to a drive system that is mostly used by cheap,entry-level turntables like the BSR 310 and the Garrard 40B.

- ← Previous page

- (Page 2 of 4)

- Next page →

“A much simpler exotic at a much more affordable price is the Clearaudio Clarify tonearm. This unique design uses a nylon thread to suspend the arm as a pivot, held in place vertically with a magnet. If no parts of the arm touch, then there is virtually no friction. Also, it prevents resonances from affecting the performance of the system.”

The earliest Well-Tempered Labs Arm was of this design in the late-’70s/early-’80s … minus the magnet to hold it in place vertically.

It was very well received at the time — after talking with the inventor, Bill Firebaugh, in ’85, I ended up with a Well-Tempered Turntable and Arm … and never looked back.

The Kef 105.2 speakers and Nakamichi electronics (PA-7, CA-5, OMS-7 CD, ST-7 tuner) are still in use today (my former wife got custody in the divorce) and sound great.

I am a big fan of Nelson Pass who did the original design and Theshold licenced to Nak.

I agree with everything you say about the Clearaudio Arm. It is brilliantly simple and works great. Think the closest thing to it is a unipivot design.