This is my first report on vinyls that are in print, or VIP for short. It might not be something just released, or an audiophile issue, but it will usually fit three criteria:

• The music must be engaging at least to my ears;

• The sound must be at least good (the original recording quality);

• It must be available, not out of print.

I might make an exception to the in-print/out-of-print rule if it’s in such abundant supply that it might as well be in-print. For instance, if you can find two or more copies on eBay, all known to be the same version in cases where there are multiple reissues, at or below $30, then I’d say it’s “available”. Or if Chad at Acoustic Sounds has it available and it doesn’t say “limited supply”, then it’s in-print as far as I’m concerned.

My experiences with Rhino releases have been a mixed bag. For the longest time, I avoided them after a few discs that sounded very “digital”. That’s not to say that a digitally sourced vinyl LP can’t sound great, because some do. Some of those earlier records had a cold analytical quality that was off-putting.

In recent years, Rhino has pushed to improve their sound and I wanted to revisit the label. My first taste was “Paranoid” by Black Sabbath, Sabbath’s most famous disc and a landmark in the genre. Compared to my original Warner Brothers pressing (US), the Rhino reissue had better midbass punch and grunt, better dynamic swings, lower distortion and a much quieter pressing. That disc is still available from some sellers, and at less than $20.

John Coltrane on Rhino

When I saw Rhino’s recent issues, I was immediately drawn to the Coltrane. I’m not nuanced enough to adequately word my admiration for the work of John Coltrane. He was able to play an incredible range of styles, from accompanist (his spectacular album with Johnny Hartman) to avant-garde. I don’t recall a jazz musician more capable of stepping into the foreground on solos, then sliding back into a tight ensemble to accompany other solos. His knowledge of chord progressions matched his prodigious technique, so he might be one of the only horn players who was capable of “comping” much like a keyboard player, choosing the most important notes to emphasize the changing chord progressions, all while taking a back seat to another soloist. I don’t recall someone who could make the most of long languid tones (his slower pieces and ballads) or literally blow you away with his technique (“Countdown” from Giant Steps always amazes me). To the vinyl…

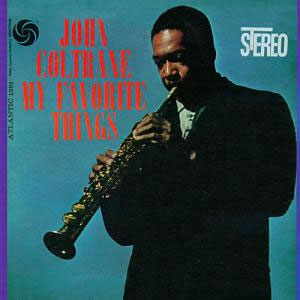

My Favorite Things

180 gram vinyl

RTI

Bernie Grundman

There isn’t a lot to say about the music here that someone hasn’t already said. Though it rates as one of Coltrane’s best selling albums, it’s not one of my favorites. It stems from my dislike of the title track, rooted in my dislike for the Broadway musical, then movie, “The Sound of Music”, overflowing with unusually trite songs for Rodgers and Hammerstein. I think the British would call it “twee”. Luckily there are three other songs that adequately compensate for “My Favorite Things”.

The performance that is somewhat jarring on first listen is Gershwin’s “Summertime”, with a modal chord progression behind a song that is neither trite or twee. Perhaps it’s not modal, but merely stretched out and augmented, vertically. There’s a musical aggressiveness, a briskness and forward momentum that makes the interpretation unique, that seems fitting for a black musician living in the ‘60s. Though still early in the civil rights movement, African Americans were starting to express themselves with more freedom. I don’t know that Coltrane ever limited himself because he was black, and that he feared “the man” would come down hard on modal chord progressions and lots of notes. I rather imagine he was influenced by the events of the day, shaping his music accordingly. Sadly, we can’t ask him.

“But Not For Me”, by Gershwin, and “Everytime We Say Goodbye”, by Cole Porter, round out the album, and both are favorite “standards” of mine. It’s equally amazing what Coltrane could accomplish with threadbare standards versus his own compositions. His performances here all sound fresh, even though all the tunes were well known. He even makes the best of “My Favorite Things”, which otherwise sucks without Coltrane playing it. With all that being said, I won’t think any less of you if you purchased it solely for the title track. Just promise you’ll listen to the rest of the album.

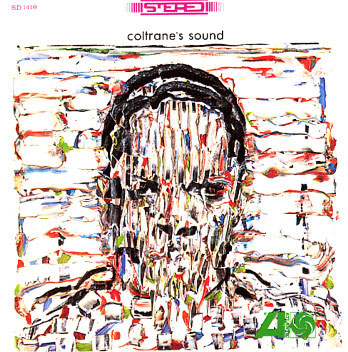

Coltrane’s Sound

180 gram

RTI

Bernie Grundman

For some reason, I managed to avoid this record for years until getting a copy of The Heavyweight Champion for Christmas. This might be the most underappreciated of Coltrane’s records. It is a collection of outtakes from the My Favorite Things sessions, recorded in 1960, but later released in 1964 after Coltrane had signed with Impulse. This was standard practice. As musicians became more popular, labels would look in their vaults for unissued tracks. Hurrah for us! Now, this might not be endorsed by the musicians because of a blown note or missed entry, etc.., but it is more like what you would hear in a live show, where notes, chords and entrances are regularly missed. I think the reasons he didn’t issue these tunes on My Favorite Things was lack of time (had to fit on a single LP) and lack of stylistic continuity (from tune to tune).

All the tracks on Coltrane’s Sound are excellent, with a version of “Body and Soul” and “Equinox”, a tune developed from “Body and Soul” (Body and Soul reharmonized and morphed into a new composition). “Body and Soul” is a tune that is more easily butchered than performed, much like the notoriously difficult “Lush Life”. “Body and Soul” was one of Billie Holiday’s signature tunes, who was stylistically a world away from Coltrane. This version is very broad, or tall, harmonically, meaning the chords are spaced further apart and augmented.

“Equinox” sounds better than some of the other tracks from these sessions: better defined bass and more solid images. The emphatic syncopated lines of the piece give it a lot more forward momentum than “Body and Soul”.

“The Night Has A Thousand Eyes” has an exotic “eastern” treatment. It does mesmerize. “Central Park West” is gorgeous. It’s the sensitive side of ‘Trane, proving he had more range than perhaps any contemporary jazz musician. My notes emphasize the vibrant and imaginative voicing of McCoy Tyner’s chords, which are a critical part of Coltrane’s sound through 1965. Without Tyner, and drummer Elvin Jones, these recordings would be dramatically different, and probably for the worse.

“Satellite” harkens back a few years to Coltrane’s hard-bop style, reminiscent of his work with Prestige. Though both albums were supposedly from the same recording sessions, the musical styles look back to his work in the late ‘50s and forward to his time at Impulse.

Rhino’s Sound

Across the board, these records are much better than earlier Rhino products. The quality of the jackets is just about perfect. They are “tip on” covers, replicating the original manufacturing techniques (more expensive to make and more solid feeling). The lithography looks as good as the originals, but without the wear and tear of 50 years. They even went to the trouble of replicating the original labels and using a stamp to literally pound “STEREO” into the face of My Favorite Things just as it was originally done. The front of the original jackets were used for mono and stereo, so someone had the job of turning the monos into stereos—I believe the back came in both mono and stereo versions.

Equally improved is Bernie Grundman’s sound, which for a time had fallen behind some of his peers. Well, the sound here is as good as I’ve heard these recordings. I went back multiple times to other pressings when listening to My Favorite Things. I have the ‘70s issue, which is good, along with The Heavyweight edition and an English Decca pressing. The Decca engineers took some liberties to correct the bass which is a little bloated on the original tapes. The tonal balance of the three US releases were very similar, but the new issue here had better surfaces, better dynamics, lower distortion and much better clarity. I heard recording artifacts on the new Rhino issue that I hadn’t heard. After carefully listening to my other pressings, I could hear them, as if they were there all along, but hiding.

I can’t say that the original recordings are “audiophile quality”, even though the recording engineer, Tom Dowd, is justly famous for his credits. There are times where it seems as if the bass was recorded slightly out of phase on a second microphone (not on all tracks), causing phase and frequency issues. On the other hand, Coltrane’s tone is beautiful, and he gets the bulk of the attention. There are some audible engineering moments, like level changes and pans, but the sound is still very good, and the music is tremendously rewarding.

What Rhino has done then, is faithfully recreate but also improve something that couldn’t really be improved on. What I mean is that the original issues sounded similar, so it’s not as if the two sound totally different. However, if you try to find a mint original pressing, you’ll quickly appreciate Rhino’s attention to detail. You likely won’t find better sounding or better manufactured jackets than these.

If you are new to Coltrane or new to jazz in general, both albums are good for beginners. There is some challenging music, but it’s not extremely experimental or atonal, so it’s easy on the ears for repeated listens. Congratulations to Rhino for doing justice to John Coltrane. Both records are highly recommended for both music lovers and audiophiles. Judging from the last few issues, Rhino is comparable to any other audiophile label, and for that I am thankful. You won’t find those other labels reissuing Black Sabbath, The Smiths and John Coltrane concurrently. Kudos for that!

- (Page 1 of 1)