Studio Recordings from Baden-Baden 1958-59

Dusko Goykovich—Trumpet

Lucky Thompson—Soprano Sax

Hans Hammerschmid—Piano

Hartwig Bartz —Drums

Rolf Kühn—Clarinet

Jimmy Pratt—Drums

Hans Koller—Tenor Sax

Attila Zoller—Guitar

Kenny Clarke—Drums

Helmut Brandt, Helmut Reinhardt, Johnny Feigl—Baritone Sax (three of them!)

Rudi Flierl—Alto Sax

Studio Recordings SWF Baden-Baden: tracks 1&2, July 15th 1959; tracks 3-7, June 14th 1959; tracks 8&9, February 24th 1959; track 10, December 2nd 1958

Side A:

1 But Not For Me

2 Sophisticated Lady

3 A Smooth One

4 O.P.

5 Minor Plus A Major

Side B:

6 Poor Butterfly

7 Anusia

8 My Little Cello

9 The Nearness of You

10 Atlantic

The life of the bass player is simpler than just about anyone else in the band. Incredible solos are not expected. Massive stage presence, or showmanship, is unnecessary. His job is to “simply” play the chord progression and help keep time. Not until small-group recordings could you even distinctly hear the bass. Early jazz groups rarely used the bass. It was difficult to record due to the awful limitations of early recording techniques. It was big, expensive and bulky. When Louis Armstrong expanded his “Hot Five” to the “Hot Seven”, he added Tuba, not bass.

With improved recording techniques and the shift from large ensembles to small, the bass player finally received name recognition. With the development of bebop and modal chord progressions, the bass player no longer sat at the back of the bus. His full understanding of advanced chord structure was crucial for the correct sound.

Where the bassist deserves more credit is as the glue, and sometimes the producer of a cohesive unit. The bassist might lead groups, compose, arrange and do the normal bassist duties, making him a Renaissance man. He holds songs together and shepherds the group through transitions and chord changes. He can play any style of music where he can learn the progressions. He probably knows the strengths of the soloist better than the soloist himself; we are poor critics of ourselves. After becoming accustomed to the bass, I am much more aware of its absence than any other instrument.

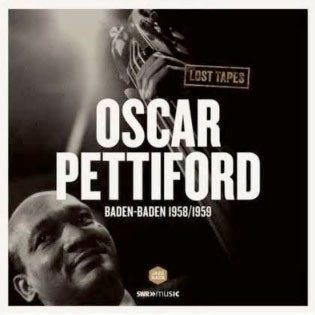

As a prime example of the Renaissance man in jazz, there is Oscar Pettiford. His Wikipedia entry is fascinating. From Okmulgee OK, not far from Charlie Christian’s birth place, he, like Charlie Christian, was an early adopter and proponent of bebop. While Pettiford led an early bop group with Dizzy Gillespie in 1944, he also played with Woody Herman, Earl Hines, Ben Webster, Coleman Hawkins, Charlie Barnet and Duke Ellington in the ‘40s. That’s a wide range of styles and leaders, and something only drummers and bassists could pull off. He stayed very active until his untimely death in 1960 at the age of 37.

In 1958, fleeing racism and looking for better prospects, as it was getting harder to find steady work in the late ‘50s, Pettiford moved to Europe, first to Baden-Baden, then to Copenhagen. Copenhagen remains a great city for jazz musicians to this day. In 1958 and 59, Pettiford recorded a number sessions for producer Joachim-Ernst Berendt in Baden-Baden, which largely went unknown until now.

This new release from Jazz Haus features inventive and interesting music, well recorded, expertly mastered and pressed on 180 gram vinyl. The album opens with “But Not For Me”, the standard by George Gershwin. It’s a charming and laid back duet featuring the trumpet of Dusko Goykovich. The recording is warm, with plenty of detail. The bass introduction is a fitting opening to the song, and the album, showcasing Pettiford’s ability as a leader.

A beautiful version of “Sophisticated Lady”, a beautiful tune by Ellington, is stripped bare. Lucky Thompson’s soprano sax solo is light and airy, but also melancholy. “A Smooth One” by fellow bebop pioneer Charlie Christian, has clarinetist Rolf Kuhn playing with warm tone and cool style, and a Pettiford playing a bouncy solo.

Many of these performances are distinctly “cool”, as in “West Coast”, or what have you. I’m not sure if Europeans had more access to the better established and international labels like Capitol, or if Europeans were genetically predisposed to the “cool school”. “O.P.”, a reference to Oscar Pettiford’s initials, was composed by soloist Hans Koller who plays a cool and angular tenor sax on several tracks. There is a delightful interchange between the clarinet and tenor sax. Like many West Coast style tracks, it is snappy and up-tempo. Rolf Kuhn’s clarinet solo steals the show.

Composed by clarinetist Rolf Kuhn, “Minor Plus a Major” opens in a mysterious fashion, with a deliberately obscure tonal center, before launching into yet another fine clarinet solo.

Raymond Hubbel’s “Poor Butterfly” opens side two with a wonderfully tuneful and contoured solo by Pettiford. “Anusia” by Hans Koller, features a solo by the composer, and an uncredited clarinet solo, swinging in a more traditional style (pre-bebop). “My Little Cello” by Pettiford, showcases the cello, an instrument that Pettiford help introduce to jazz audiences after he broke his arm some years earlier. While his arm was healing, the cello was his only option. The West Coast styled composition features a long tenor solo by Koller. The tune, as well as the solo by Koller, is a toe-tapper.

“The Nearness of You” is a perfect vehicle for Pettiford’s lyrical approach to soloing. Very few versions of this song do anything for me, and this one is easily the most interesting I’ve heard. Pettiford’s lines are finely crafted, with phrasing as good as any wind instrument or vocalist.

The album closes out with one of the coolest jazz performances I’ve heard. “Atlantic” features the baritone sax playing of the composer Helmut Brandt, along with that of Helmut Reinhardt and Johnny Feigl. The trio of bari sax players pump out an amazing sound, something like exploding trees and velvet. The chords are imaginative and the timbre of the ensemble encourages the listener to crank up the volume. The brisk tune is an assault on the senses, and could’ve been the theme song of a ‘60s TV show.

All the recordings on this album vary in perspective and sound, along with changing instrumentation. Like the music, the sound is universally good, with some tracks being audiophile caliber. The mastering and pressing are first rate. Most surprising to me is the playing of Kuhn and Koller, who could hold their own against more famous players from the US. This album is a delight, and serves as a memorial to, and reminder of, the greatness of Oscar Pettiford.

- (Page 1 of 1)